Gambling and financial harms: a multi-level approach

Virve Marionneau¹, Janne Nikkinen¹

¹University of Helsinki

This non-peer reviewed entry is published as part of the Critical Gambling Studies Blog. To cite this blog post: Marionne, V. & Nikkinen, J. (2024). Gambling and financial harms: a multi-level approach. Critical Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.29173/cgs179.

Introduction

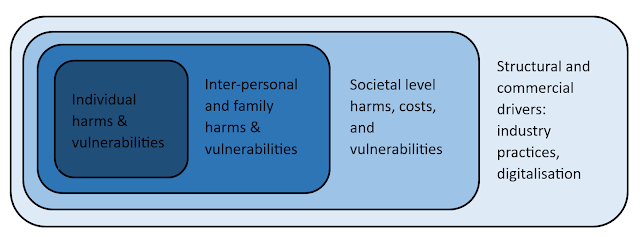

Gambling

is integrally linked to financial problems and harms. In this blog, we discuss

the relationship between gambling and financial harm from a multi-level, socio-ecological

perspective (cf. Wardle et al., 2018). We argue that gambling and financial

harms are linked in a multitude of ways, spanning far beyond the individual

experience of debt and financial hardship. Gambling can lead to significant

financial losses that have wide-ranging and rapidly emerging negative impacts

on individuals and families. Financial harms caused by gambling are also

experienced at inter-personal and societal levels. These harms are driven by

individual vulnerabilities as well as social structures, including commercial

exploitation and increased availability of both gambling and credit,

particularly in digital environments. A model of a socio-ecological approach to

gambling and financial harm is presented in Figure 1.

|

| Figure 1. A socio-ecological approach to gambling and financial harm. |

Individual and inter-personal levels

Gambling can cause financial harm to individuals and families when they cannot meet other financial commitments due to gambling, or when they borrow money to finance continued gambling (Muggleton et al., 2021; Barnard et al., 2014). Gambling-related financial harms can further aggravate other gambling-related harms. Financial difficulties may cause or worsen health issues, psychological suffering, and family disfunction (Swanton & Gainsbury, 2020a). Debt and financial trouble are also key drivers behind gambling-related suicidality (Marionneau & Nikkinen, 2022). A UK study found that high levels of gambling were associated with 37% increase in mortality (Muggleton et al., 2021). Similar harms accrue at the inter-personal level. Family members of those experiencing problems with gambling can also experience long-term financial harms. Financial hardship puts a two-fold strain on families: gambling-related debt and financial losses impact the family household budget, but they also have a negative impact on family relationships and emotional wellbeing (Marionneau et al., 2023b; Dowling, 2014).

Levels of debt have been found to be particularly high among help-seekers and those meeting the clinical criteria for problem gambling (Downs & Woolrych, 2010; Swanton & Gainsbury, 2020b). Recent studies using bank transaction data (Davies et al., 2022; Marionneau et al., 2023a) have found that gambling is prevalent also among those seeking help for financial problems at debt consolidation or consumer credit counselling services. For example, we recently conducted study using past-year bank transaction data of highly indebted Finnish individuals seeking a debt consolidation loan (N=23,231) (Marionneau et al., 2023a). The results of this study showed that 55.8 percent of these highly indebted individuals had gambled in the previous year (excluding cash-based gambling) and approximately 17 percent (N=4,006) of applications for debt consolidation within the service were rejected due to heavy gambling. This is particularly alarming since this may discourage individuals experiencing gambling harm from seeking other help.

Financial problems are not only a cause of gambling, but they can also be an important driver of gambling. Accumulated debt may encourage further gambling as a perceived solution (Sulkunen et al., 2019). Financial difficulties related to gambling may also differ across socio-demographic characteristics. Gambling expenditure is highly concentrated at a population level (e.g., Kesaite et al., 2023). Those in the highest spending groups are more often male and have lower educational levels than those in lowest spending groups (e.g., Grönroos et al., 2021). These social groups may also be more vulnerable to financial problems due to their gambling.

Societal level

Gambling is also linked with financial harm at a societal level. Gambling generates a range of societal costs, spanning from cost of illness to enforcement costs and productivity related issues (e.g., Hofmarcher et al., 2020). In addition, gambling is linked to many intangible costs and harms. Costs are not the same as harms, and not all harms can be calculated as monetary costs. Intangible costs and harms include reduced quality of life but also more societal issues such as inequalities and poverty (Hofmarcher et al., 2020; Sulkunen et al., 2019). Many societal level harms are also not a direct result of problematic gambling, but of gambling provision more generally (Nikkinen & Marionneau, 2014). For example, gambling consumption may substitute other forms of consumption that could be equally or even more productive for societies (Marionneau & Nikkinen, 2020). The gambling industry may also be particularly prone to different types of illegal activity, including corruption, and money-laundering (Banks & Waugh, 2019).

Societal-level drivers may contribute to increased gambling-related financial harm. Societies differ in terms of gambling availability, accessibility, and acceptability. The framings and justifications of gambling legislations within societies also have a direct impact on what kind of policy measures are implemented (Ukhova et al., 2023). For example, if gambling is primarily seen as a vehicle for public finance rather than as a health-harming and addictive commodity, the regulatory response will favour tools that highlight individual responsibility over more public health-oriented measures, such as limiting availability (Cassidy, 2020; Ukhova et al., 2023, Aimo et al., 2023). These differences have direct implications for the emergence of financial harms for individuals, families, and societies.

Structural and commercial drivers

Commercial determinants of harmful gambling are increasingly well known (e.g., de Lacy-Vawdon et al., 2023; Reith & Wardle, 2022). For example, the gambling industry has been shown to wield different forms of soft and hard power over consumers and regulatory action (de Lacy-Vawdon et al., 2023). This power is visible in actions such as marketing, product design and preference-shaping, but also in political agenda setting and framing, direct relationships with decision-makers, and industry influence over research (de Lacy-Vawdon et al., 2023; Johnson et al., 2023; Reith & Wardle, 2022; Adams, 2022; Cassidy et al., 2013). These power structures span beyond the gambling industry, and link to wider societal processes such as neoliberal capitalist ideology, globalisation, and financialisation (de Lacy-Vawdon et al., 2023; Reith 2013; Nicoll, 2013).

Similar determinants drive the financial credit and particularly high-cost instant or payday loan industries. Instant loans and consumer credit have become abundantly prevalent and easy to access. In some societies, instant loans are extensively advertised and pushed to consumers, often resulting in high levels of indebtedness (Majamaa & Lehtinen, 2022; Hiilamo 2018). The commercial determinants behind financial harm can therefore span beyond the gambling industry, intersecting with the credit industries as well as a network of other commercial interests (also Marionneau et al., 2023a).

Gambling and credit industries employ similar tactics to exploit the vulnerabilities of consumers for profit. Commercial gambling extracts value from the assets and savings of consumers (Young & Markham, 2017). This exploitation can be expanded using credit. The wide availability of credit, and particularly instant loans, is connected to excessive gambling spending and debt (Swanton & Gainsbury, 2020b; Marionneau et al., 2023a). For example, the landmark study by Muggleton et al., (2021) using bank transaction data of British consumers (N=6,500,000) showed that a ten percent increase in gambling consumption was connected to a 11.2 percent increase in credit card usage, as and a 51.5 percent increase in high-cost payday loans. In comparison to non-gamblers, those gambling were 400 percent more likely to take payday loan in the next month. In our study of individuals seeking debt refinancing (Marionneau et al., 2023a), we found that individuals with unsecured loans (such as instant loans and pay-day loans) had lost significantly more money in gambling in the past year than individuals without unsecured loans.

Advances in digital technology are likely to accelerate the commercial drivers behind gambling-related financial harm. Gambling products are increasingly provided via digital channels. Digital gambling products are typically designed to increase time-on-device, amplifying addiction as a design element (Schüll, 2012; see also Gottlieb et al. 2021). Digital channels also make access to credit easy and debt even faster to accumulate. Digitalisation is likely to be another driver behind financial harm caused by gambling. Digitalisation may also further increase the reciprocity between the gambling and credit industries: The provision and production of digital gambling involves a wide network of actors, such as payment intermediaries, that may be directly linked to banks and credit institutions.

Digital environments produce vast amounts of data that can be used to help individuals set personal limits. Such tools, also known as ‘responsible gambling tools’ can help some individuals in controlling their gambling – but they continue to not address the systemic issues that drive harms. Data generated in digital environments could be used to identify harmful gambling behaviours for targeted interventions (Marionneau et al., 2023c). However, the bulk of data-driven interventions are implemented and developed by gambling industry actors for corporate social responsibility purposes. Furthermore, these same data are also actively used by gambling companies to target consumers with marketing and more attractive offer, and to drive increased consumption. From a public health perspective, data-driven interventions would be more effective if they targeted identifying and preventing exploitative industry practices.

Ways forward?

This blog has discussed the possibility of applying a socio-ecological approach to conceptualising the multi-level relationship between gambling and financial harm. Gambling and financial harm have a reciprocal relationship: Gambling is an important driver of financial harm for individuals, families, and societies. At the same time, financial harm, as well as the credit industry are also important drivers of gambling. These intersections between technology, capital, and financial interests form a complex political economic system that is still not sufficiently well understood. More research focus should be put particularly on exploring how the gambling and financial credit industries are interlinked.

A socio-ecological understanding that spans beyond individual vulnerabilities, spending habits, and money management can contribute to destigmatising gambling-related financial harm. Besides supporting individual financial literacy, approaches to limit gambling-related financial harm should also include systemic approaches, including more stringent control on the provision, availability, and marketing of gambling as well as instant loans.

More international and inter-sectoral collaboration is also needed. Globalised industries cannot be effectively regulated at national levels. At the same time, the regulation of the increasingly online-first business models of the gambling and credit industries could benefit from collaboration with other sectors. Notably, banks and payment intermediaries could be enlisted to detect and even prevent harmful consumption and exploitative practices. These types of approaches require that the relationship between gambling and financial harms is well understood at different levels, and that instead of focusing on individual vulnerabilities, regulations primarily target harmful structural and industry practices.

Virve Marionneau is the director of the University of Helsinki Centre for Research on Addiction, Control, and Governance (CEACG).

Janne Nikkinen is a university researcher at the the University of Helsinki Centre for Research on Addiction, Control, and Governance (CEACG).

The authors are funded by the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health and the Academy of Finland.

References

Adams, P. (2022). Ways industry pursues influence with policymakers. In The global gambling industry: Structures, tactics, and networks of impact (pp. 199–215). Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

Aimo, N., Bassoli, M., & Marionneau, V. (2023). A scoping review of gambling policy research in Europe. International Journal of Social Welfare.

Banks, J., & Waugh, D. (2019). A taxonomy of gambling-related crime. International Gambling Studies, 19(2), 339-357.

Barnard, M, Kerr, J, Kinsella, R, Orford, J, Reith, G, & Wardle, H. (2014). Exploring the relationship between gambling, debt, and financial management in Britain. International Gambling Studies 14, 82-95.

Black, D., Coryell, W., Crowe, R., McCormick, B., Shaw, M., & Allen, J. (2015). Suicide ideations, suicide attempts, and completed suicide in persons with pathological gambling and their first‐degree relatives. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior, 45(6), 700-709.

Cassidy, R. (2020). Vicious games. Gambling and capitalism. London: Pluto Press.

Cassidy, R., Loussouarn, C., & Pisac, A. (2014). Fair game: Producing gambling research. Goldsmiths, University of London.

Davies, S, Evans, J, & Collard, S. (2022) Exploring the links between gambling and problem debt. The Personal Finance Research Centre at the University of Bristol.

de Lacy-Vawdon, C., Vandenberg, B., & Livingstone, C. (2023). Power and other commercial determinants of health: an empirical study of the Australian food, alcohol, and gambling industries. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 12(1), 1-14.

Dowling, N. (2014). The impact of gambling problems on families. Australian Gambling Research Centre, Australian Institute of Family Studies. Final Report.

Downs, C. & Woolrych, R. (2010) Gambling and debt: The hidden impacts on family and work life. Community, Work & Family, 13(3), 311-328.

Nicoll, F. (2013). Finopower: Governing intersections between gambling and finance. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, 10(4), 385-405.

Gottlieb, M., Daynard, R., & Friedman, L. (2021). Casinos: An addiction industry in the mold of tobacco and opioid drugs. University of Illinois Law Review, 1711-1730.

Grönroos, T., Kouvonen, A., Kontto, J., & Salonen, A. H. (2021). Socio-demographic factors, gambling behaviour, and the level of gambling expenditure: A population-based study. Journal of Gambling Studies, 1-17.

Hiilamo, H. (2018). Household debt and economic crises: Causes, consequences and remedies. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Hofmarcher, T., Romild, U., Spångberg, J., Persson, U., & Håkansson, A. (2020). The societal costs of problem gambling in Sweden. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1-14.

Johnson, R., Pitt, H., Randle, M., & Thomas, S. (2023). A scoping review of the individual, socio-cultural, environmental and commercial determinants of gambling for older adults: implications for public health research and harm prevention. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 1-15.

Kesaite, V., Wardle, H., & Rossow, I. (2023). Gambling consumption and harm: a systematic review of the evidence. Addiction Research & Theory, doi: 10.1080/16066359.2023.2238608

Majamaa, K., & Lehtinen, A. (2022). An analysis of Finnish debtors who defaulted in 2014–2016 because of unsecured credit products. Journal of Consumer Policy, 45(4), 595-617.

Marionneau, V., & Nikkinen, J. (2020). Does gambling harm or benefit other industries? A systematic review. Journal of Gambling Issues 44, 4-44.

Marionneau, V., & Nikkinen, J. (2022). Gambling-related suicides and suicidality: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13:980303. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.980303

Marionneau, V., Lahtinen, A., & Nikkinen, J. (2023a). Gambling among indebted individuals: an analysis of bank transaction data. European Journal of Public Health, ckad117.

Marionneau, V., Järvinen-Tassopoulos, J., & Pirskanen, H. (2023b). Intimacy, relationality and interdependencies: relationships in families dealing with gambling harms during COVID-19. Families, Relationships and Societies, 1-21. doi: 10.1332/20467435Y2023D000000003

Marionneau, V., Ruohio, H., & Karlsson, N. (2023c). Gambling harm prevention and harm reduction in online environments: a call for action. Harm reduction journal, 20(1), 92.

Muggleton, N., Parpart, P., Newall, P., Leake, D., Gathergood, J., & Stewart, N. (2021). The association between gambling and financial, social and health outcomes in big financial data. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(3), 319-326.

Nikkinen, J., & Marionneau, V. (2014). Gambling and the common good. Gambling Research, 26 (1), 3-19.

Reith, G. (2013). Techno economic systems and excessive consumption: A political economy of ‘pathological’ gambling. The British Journal of Sociology, 64(4), 717-738.

Reith, G., & Wardle, H. (2022). The framing of gambling and the commercial determinants of harm: Challenges for regulation in the UK. In The global gambling industry: Structures, Tactics, and Networks of Impact (pp. 71-86). Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

Schüll, N. (2012). Addiction by design. Machine gambling in Las Vegas. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Sulkunen, P., Babor, T., Cisneros Örnberg, J., Egerer, M., Hellman, M., Livingstone, C., Marionneau, V., Nikkinen, J., Orford, J., Room, R., & Rossow, I. (2019). Setting limits: Gambling, science, and public policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Swanton, T. & Gainsbury, S. (2020a) Gambling-related consumer credit use and debt problems: A brief review. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 31, 21-31.

Swanton, T., & Gainsbury, S. (2020a) Debt stress partly explains the relationship between problem gambling and comorbid mental health problems. Social Science & Medicine, 265:113476. doi: 0.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113476

Wardle, H, Reith, G, Best, D, McDaid, D, & Platt S. (2018). Measuring gambling-related harms: a framework for action. Gambling Commission, Birmingham, UK.

Young, M., & Markham, F. (2017) Coercive commodities and the political economy of involuntary consumption: The case of the gambling industries. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49(12), 2762-2779.

Comments

Post a Comment