GameBling Game Jam 2.0: The Writing Workshop

GameBling

Game Jam 2.0:

The Writing Workshop

Pauline Hoebanx* & Hanine El Mir*

*Concordia

University

This non-peer-reviewed entry is published as part of the Critical Gambling Studies Blog. To cite this blog post: Hoebanx, P., & El Mir, H. (2024). GameBling Game Jam 2.0: The writing workshop. Critical Gambling Studies Blog. https://doi.org/10.29173/cgs192

This

is a short introduction to a series of blog posts, below, written by

participants in the second edition of the GameBling Game Jam.

GameBling 2.0

On

the 11th and 12th of February 2023, Concordia University hosted the second

edition of the GameBling Game Jam, one year after the successful first

edition (Hoebanx et al., 2023). A game jam is an event during which individuals

or teams attempt to create a game from scratch in a limited amount of time. A

detailed explanation of game jams and a summary of the first edition can be

found in Hoebanx et al. (2023).

In

Hoebanx et al. (2023), we argued that game jams can be used as an innovative

research method “that can help uncover new ways to think about and question

social science concepts.” We put that idea to the test again in the second

edition, with an added twist: we held a writing workshop after the event to

which all jam participants were invited. Of the 16 original participants,

9 participated in the writing workshop. The primary goal was to encourage

jam participants to reflect on and write about their experiences as game

designers, aiming to gain insights into their thinking and design

processes—something that last year’s blog post was not able to achieve (Hoebanx

et al., 2023). The blog posts in this series are the result of this writing

workshop.

While

the theme of the first edition was slot machines, the second edition’s theme

was more abstract: (Un)Lucky. Supported by TAG—the Technoculture, Art and Games Research Centre,

housed in the Milieux Institute for

Arts, Culture and Technology at Concordia University—along with the

research teams at Concordia’s Research

Chair on Gambling—HERMES and Jeu

Responsable à l’Ère Numérique (JREN)—the jam hosted sixteen participants,

the same number as the previous edition. The event was virtual and took place

over Discord and the Gathertown platform. Participants received a $300 bursary

for their participation. Accompanied by four organizers and a floating mentor,

six teams generated eight unique games, which were uploaded to the itch.io page

(GameBling Game Jam 2.0, 2023). Participants had the option to present

game ideas or working game design documents without the requirement of a

finished game on the itch.io page. The organizers emphasized the low-stakes,

exploratory nature of the event and highlighted its experimental space, which

encouraged collaboration, diverse roles, and various interpretations of the

theme.

GameBling 2.0 Event Banner

The

organizers were interested in the outcome of a theme that did not dictate a

specific game mechanic; unlike the previous year, which had called for a focus

on slot machine retention mechanics. As a result, the games that were created

included three card games, an adventure game, a coin-flipping game, and a horse

race betting game. All the games are available to play here.

(Note: STEAKdotORG was not submitted by a

participant in the Game Jam.)

Four

blog posts came out of the writing workshop and focused on the following games:

Luck of the Draw, Charming Offering, Cat Luck, and Flip

a Coin. These blog posts illustrate some of the ways that jam participants

interpreted the theme and later made connections between the theme and

scholarly work about luck, gambling studies, and even drama studies. Unlike the

initial game jam, where all six games portrayed slot machines negatively, our

recent edition presented a more varied perspective. Among the featured games,

only Flip a Coin depicted the hazards of gambling, while the others did

not associate gambling with negative undertones. This shift can be attributed

to the more abstract prompt, (Un)Lucky, which encouraged participants to focus

on the concept of luck rather than on a specific game, since that might carry

pre-existing negative connotations in the collective imaginary.

Through

the facilitation of game jams that prompt participants to contemplate gambling,

our aim is to uncover innovative research methods as valuable tools for

thinking about gambling. As advocated by several critical gambling studies

scholars (e.g., Cassidy et al., 2015; Reynolds et al., 2020), there is a need

for more interdisciplinary research in gambling studies, extending beyond the

conventional clinical and quantitative research. Broadening our comprehension

of gambling experiences and exploring the ways gambling is depicted in our

collective imagination is crucial. This approach reveals nuanced facets of how

gambling is experienced and imagined, and it can guide us toward potential

interventions if necessary.

In

light of this, we invite you to read the posts in this special section of the Critical

Gambling Studies Blog by reflecting on how we can use innovative research

methods to expand the ways we think about and study gambling.

References

Cassidy, R., Pisac, A., & Loussouarn, C.

(Eds.). (2015). Qualitative research in gambling: Exploring the production

and consumption of risk. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203718872

GameBling Game Jam 2.0. (2023, February 11). itch.io. https://itch.io/jam/gamebling-game-jam-2

Hoebanx, P., Isdrake, I., Kairouz, S., Simon, B.,

& French, M. (2023, March 13). The GameBling Game Jam: Game jams as a

method for studying gambling games. Critical Gambling Studies Blog. https://doi.org/10.29173/cgs160

Reynolds, J., Kairouz, S., Ilacqua, S., &

French, M. (2020). Responsible gambling: A scoping review. Critical Gambling

Studies, 1(1), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.29173/cgs42

Luck of the Draw:

Card Games, Superstitions, and Cats

Leonardo Abate

I

participated in the GameBling Game Jam 2.0 alongside Justin Roberts and

E. Jules Maier-Zucchino, taking the name Team Pasta Casa after an inside joke

too long to recount here. Our entry for the jam, Luck of the Draw (Team

Pasta Casa, 2023), is a simple game of chance inspired by the trappings of the

draft tournament format in trading card games (TCGs). The player is presented

with a random selection of three cards from which they must pick one; this

process is repeated over five rounds, resulting in a hand of five cards. Cards

can be lucky or unlucky, and are worth an equal amount of good or bad luck,

with the exception of rarer cards (lucky number 7 and unlucky number 13),

which are worth more points. After the five-card hand is completed, players are

then presented with a random test that can benefit from either good luck or bad

luck. A 20-sided die is rolled, and the result is added to the amount of good

or bad luck accumulated. If the total result is 15 or more, the game is won.

Otherwise, it is lost.

There

are also two secret ending scenarios, which can be accessed by constructing

specific hands: one is unlocked if good and bad luck are balanced (i.e., there

is at most one point of difference between the good and bad luck scores), the

other if the player picked at least three cat-based cards (the tortoiseshell

cat, maneki-neko, and / or the black cat). In both cases, there is no

test, and the player is considered to have won automatically.

Thought Process and Expectations during Development

Coming

into the brainstorming portion of the jam, our lead programmer, Jules,

immediately had the idea of using a draft (a popular tournament format of the

TCG Magic: The Gathering) as the basis for our game design, as it is

something that we all had experience with and it fit the theme of “luck” very

well. A Magic draft tournament requires players to open a set amount of

booster packs provided by the venue, select a card from each, and pass the rest

to a player seated next to them; repeating the process until enough packs have

been opened and cards collected for a full deck to be formed. It is a format

that rewards knowledge of the game’s strategy to construct a functional deck

out of the available pool of cards, but it is also eminently based on luck,

which determines what opportunities are being presented to each player.

With

that baseline in mind, we decided to move away from the multiplayer aspects of Magic

(as they felt too complex to tackle within the scope of the jam) and tried to

recapture the feeling of building a viable strategy out of the limited

possibilities available. We decided to style the cards after good luck charms

and bad luck omens from popular folklore in order to stay within the game

theme, to give players familiar with the symbols an intuitive understanding of

the cards’ relative value, and to introduce those unfamiliar to superstitions

from different cultures. Our hope was to use the trappings of a draft game and

the intuitive understanding of good and bad luck to trick the player into value

judgments about the cards (leading them, for example, to avoid bad luck cards

and aim for good luck cards on a first run), while simultaneously using the

ending scenarios to showcase an equivalence of the two types of luck, rewarding

balance rather than obsession of one over the other.

We

initially toyed with more complex design ideas—such as having poker suits

represent different “types” of luck that could be collected (instead of the

simplistic good and bad luck that we went with in the end), cards having more

unique properties, and the final event be some kind of battle scenario that

would require the playing of collected cards to win—but we scrapped these due

to the jam’s time constraints. This ended up being a good call, as it allowed

us to complete the game in time without too much stress, and the thematic

intentions were not undercut by the simplicity of the final game.

Reflections on the Theme of Luck

We

toyed extensively with the theme of luck, as it appears in the game on four

different layers of experience. Firstly, luck is presented in the game’s

aesthetics: all the cards are styled after charms and ill omens from folklore

of different cultures, which we researched during production. We would have

liked to have more in-depth descriptions of the symbols used to potentially

give players some insight into the origin of these folkloristic traditions, but

this feature too was scrapped for time, and we settled instead on witty flavour

text for each card that hints at the origins of each symbol. The use of

pre-existing symbology for luck also helped our intent of priming the player to

expect certain cards to be “better” than others while subverting that belief in

the rules themselves. We even decided to never state the rules explicitly in

the interest of leaving the player’s intuitive assumptions as the only

guidelines when they first play the game.

Figure 4. An example of some lucky cards.

The

hidden layer of this reflection is that, due to the secret scenarios, the ways

to reliably “win” the game have very little to do with luck as presented. This

was not planned from the start as an explicit goal: we included the secret

endings mainly because they sounded fun. But, in an appropriately serendipitous

twist, we realized after testing the game that their implied rhetoric worked

nicely within the larger context of the game. One secret scenario rewards

balancing good luck with ill omens and accepting the ups and downs in fortune

as the wisest course of action, while the other secret scenario rewards a

player that ignores the symbolic lucky or unlucky judgment placed on the cards

in favour of pursuing that which makes one happy (i.e., cats).

We

had hoped to make the secret scenarios achievable in every session. We wanted

them to be a method to bypass the quantified abstraction of luck present in the

internal mechanics of the game. However, we were unfortunately unable to

completely remove the element of randomness, as the secret scenarios still rely

on the pool of cards presented to the player to be achieved. In other words,

while the secret scenarios might be easier and more reliable outcomes to

achieve for the player (balance good and bad luck, or pick three cat cards),

they still might be impossible to reach if presented with a bad draft of cards.

As it turns out, it’s hard to build an engaging game based on luck while also

including solutions that do not rely on chance at all.

Figure 5. The good luck standard ending.

Critical Theorization

Beside

what has already been said about the expectations created by symbols of good

and bad luck, there are two ways in which this game can be put into

conversation with larger critical analyses of gambling and luck. The first is

within the confines of TCGs and their competitive scene. Draft tournaments are

a popular format for TCG competitions, pulling together the various

characteristics that makes the medium successful: their nature as collectibles

(where participants at draft tournaments can keep the cards they drafted and /

or win more cards through the event), as a strategy game (knowledge of the

system is rewarded when constructing a drafted deck), and finally, in the

innate gambling aspect of booster packs. Luck in TCGs is used as a tool for

fairness both within a game (what cards one ends up drawing) and at a referee

level (drafting allows for an impartial, if rarely equal, distribution of

resources); but it is also a commercial snare, as the chance of getting a good

card is used as incentive for buying multiple booster packs (Martin, 2019). Our

game disrupts this framework (albeit somewhat inadvertently) by making the

card-collecting aspect deceptively useless: most cards are equivalent in value

and strategic worth, including the bad luck ones (which a first-time player

might avoid because of their negative connotations), and even if there are ones

that are rarer than others, their collection doesn’t necessarily equate to a

better final result (as the winning strategies remain pursuing balance and

cats, rather than leaving the outcome of the game entirely up to chance).

The

second framework of analysis that could be applied to the game is that of

rituals. As mentioned, all the cards in the game are styled after charms and

ill omens, whose collection grants a quantified representation of luck. In

gambling culture, there is a tendency to maximize one’s luck through rituals

and by avoiding unlucky gestures, circumstances, or symbols (Grunfeld et al.,

2008), which showcases a practical understanding of luck as something that can

be accumulated, or at the very least attracted. This value judgment on certain

things and actions as “lucky” or “unlucky” can be harmless, but it can also

combine with misunderstandings of probability to produce a worse relationship

with gambling. In our game, lucky and unlucky symbols are presented as

qualitatively distinct but morally neutral, without one being innately “better”

than the other in all circumstances, and both being required for the best

endings. This follows a similar logic to the Taoist parable of “The Farmer’s

Luck,” which we were reminded of during development:

There was once an old farmer who had worked his

crops for many years.

One day his horse ran away. Upon hearing the news,

his neighbors came to visit.

“Such bad luck,” they said sympathetically.

“Maybe,” the farmer replied.

The next morning the horse returned, bringing with

it two other wild horses.

“Such good luck!” the neighbors exclaimed.

“Maybe,” replied the old man.

The following day, his son tried to ride one of the

untamed horses, was thrown, and broke his leg.

Again, the neighbors came to offer their sympathy

on his misfortune.

“Such bad luck,” they said.

“Maybe,” answered the farmer.

The day after, military officials came to the

village to draft young men into the army. Seeing that the son’s leg was broken,

they passed him by.

“Such good luck!” cried the neighbors.

“Maybe,” said the farmer.”

(Ying, 2018)

Ultimately,

it’s hard to know what exactly “good luck” or “bad luck” are. Life’s events are

unpredictable, and both good and bad fortune can lead to positive or negative

consequences depending on your perspective. It is perhaps better, then, not to

consider luck in decision-making at all, and instead simply try to collect

cats.

Figure 6. The secret cat ending.

Luck of the Draw

can be played here

Sources

Grunfeld, R., Zangeneh, M., & Diakoloukas, L.

(2008). Religiosity and gambling rituals. In M. Zangeneh, A. Blaszczynski,

& N. E. Turner (Eds.), In the pursuit of winning: Problem gambling

theory, research and treatment (pp. 155–165). Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-0-387-72173-6

Martin, M. (2019). Magic: The Obsession. New

Errands: The Undergraduate Journal of American Studies, 6(2). https://doi.org/10.18113/P8ne6261229

Team Pasta Casa. (2023). Luck of the Draw

(Online Version) [Video Game]. itch.io. https://emzsilversound.itch.io/luck-of-the-draw

Ying, J. (2018, March 6). Taoist story: The

farmer’s luck. Living the Present Moment. https://livingthepresentmoment.com/taoist-story-farmers-luck

On Making Charming Offering:

GameBling Game Jam 2023

Isabella Byrne & Calvin Lachance

Over

the course of a February weekend, Calvin Lachance, Isabella Byrne, and Che Tan

formed one of the teams in the second edition of the virtual GameBling Game

Jam presented by JREN, TAG, HERMES,

Research

Chair on Gambling, and Concordia University to build a game that would

touch on the relationships between luck, play, and gambling.

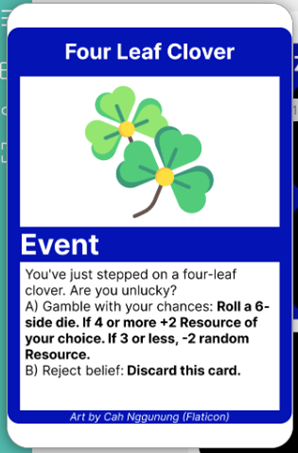

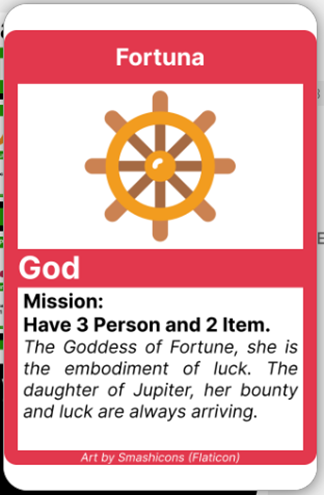

Our entry, Charming Offering, is an analog single-player card game focused on collecting luck-infused offerings for a pantheon of gods. At the start of the game, you randomly pick two gods, each of whom demands specific resources in exchange for bestowing their good luck upon you. You win the game and gain the favour of your chosen gods when you collect all of the requested resources. Resources are gathered by strategizing through a limited number of story events, which either grant or require resources to proceed.

Thoughts on the Process

Calvin:

With tight timelines being constitutive of this game jam, our fixed working

period informed the parameters through which we prioritized tasks, built our

scope, and moulded the final product. Our weekend time-limit was more

circumstantial than constrictive. Despite possessing fewer game-design skills,

I was comfortable with my first game jam project taking the form of an analog

card game; it was well-suited to our collective ideas, experiences, and vision.

The game that I initially imagined had too large a scope for a weekend project.

In the drafting stages, I had hoped for us to create a heavily narrativized

game that would incite the player to reflect on their own relationship to and

beliefs about luck. With more time, I would have enjoyed seeing our team craft

a more detailed narrative that was thematically framed by luck and fortune and

would pertain to in-game items and characters. Within this thematic framework,

players’ gaming experiences would be enriched.

Isabella: We

spent most of the weekend trying to translate our concept into a playable game.

Over the two days, we felt tensions between sticking to our desired themes and

the functional mechanics of the game. At times, we stuck too closely to our

theme, which resulted in a game that wasn’t really fun to play; it did not seem

to have any end goals. We reconfigured the game by adhering to playing card

game mechanics. However, this contributed to feeling like we had distanced

ourselves from our initial idea that inspired us to create the game.

Additionally, in both cases, the games we planned had too broad of a scope to

accomplish over one weekend.

We had to learn (quickly!) how to balance critical

theory with designing a workable game by integrating both features’ essential

elements. We would spend some time discussing the desired theme, then we would

move away from it to focus on the game’s mechanics, and then assess whether we

had successfully woven the two together. What took us the longest was the

process of achieving a concrete idea; during this time, we went through many

different iterations of the game. Finally, once we made the initial prototype,

it was tweaked after playtesting.

Addressing the Theme

Isabella: My

greatest challenge was coming at this process from a writing background rather

than game design. In game design, your point is communicated through inference

in the active play the player undertakes. I felt pressure to “make this game

academic,” as the game jam was taking place within a university context and was

meant to address certain areas of scholarship. I struggled to reconcile the

tension of making a game that was fun while having it “say something,”

especially when adding important context for our themes was not workable

through our medium.

Calvin: As

I discussed previously, I was far more comfortable working with themes and

stories than with logistics. The theme of luck is exceptionally interesting to

me, imbued with a plethora of spiritual, cosmic, and religious aspects that I

hoped to explore. In light of humanity’s long history of attributing the

unknowable or uncertain to the actions of gods, I was intrigued by our

historical relationship between luck and the divine or spiritual. I was also

interested in how mundane items or practices can shape the criteria by which we

measure what is human and what is beyond human. Early on, my teammates

introduced the idea of sitting next to a “lucky person,” introducing the notion

of luck transference through proximity. I thought this was brilliant, and quickly

became attached to incorporating these themes in the final game. And so began

the process of accumulating a series of items and practices that could be

perceived as having an ability to hold, transfer, or negate luck. We

crowdsourced some ideas from other game jam members for our event cards,

prompting them to share some items or rituals which they engaged in.

Incorporating personal accounts into our resource and event cards was another

way, I believe, to integrate humans’ relationships to luck, marked by unique

perception and understanding.

Figure 2. Examples of event cards.

Turning the Theme into a Game

Calvin:

Following research on gods of luck, my personal relationship to the theme was

enhanced by the game-making process. Since I had no experience in game

creation, my team provided some amazing suggestions of card-based games to help

guide us to the final product: games such as FLUXX and Underhand. Additionally,

my research on luck gods provided me with tremendous insight into the cultural

and historical contexts that shaped the relationships between individuals and

luck, and into how we render intelligible these intangible, elusive, and

ephemeral phenomena. Working in a team of brilliant individuals with their own

ideas of luck inevitably shaped how I engaged with and metabolized the theme by

the end of our project.

Figure 3. Examples of God cards.

Conducting research into specific gods of luck

allowed me to explore how the concept of luck can be gamified in a myriad of

ways and what threads connect these possibilities. I realized that, in working

through this theme, luck extends beyond the scope of human capacity and action;

that it is so often understood to be external to us, and out of our control.

Simply put, the game’s goal is to meet a god of luck by engaging in events and

gathering resources. In our game, of course, the randomization of cards (some

representative of bad luck, some of good) working in tune with player

strategizing to meet their goal was one way to exercise the flux of situational

or circumstantial control; by this, I mean where an individual’s actions can

shift outcomes and where it can’t. Many games, even the simplest, take this

shape: you are never wholly lucky or wholly strategic—you are always engaging

in calculated chance. Personally, I wanted our game to feel like a small but

enjoyable exercise in the humanization of luck.

Isabella:

When I heard that we were supposed to make games around luck for this year’s GameBling

Jam, I was excited to think about the relationship between luck,

materiality, and other forms of ritual actions or objects involved in play that

give the player an impression of control over the game. While the game we

finally created involved these themes, we found the process of designing it

with them in mind to be challenging. In this way, this game jam was a good

primer in learning how to turn a concept into a product. I was challenged by

the process of exploring these themes versus creating a finished product. I

felt more intrigued by simply seeing how games were made and playing with this

scholarly area than creating a completed game. Ultimately, I think we struck a

good balance.

What We Learned about Game Design

Isabella:

This process taught me a lot about the importance of iteration in game design.

The game iteratively improved following testing some aspect and then critically

analyzing it. I have no doubt that we could go back to our completed game and

take it apart to make something even better. Iteration appears to be one of the

foundational cornerstones of game design. Each new version was unique and could

have been its own successful version of a game that addressed the theme, but as

we reformed the game with each encounter, we improved it until it became the

best workable product of itself. This process gave me an immense amount of

respect for game designers, especially ones who work on projects much larger

than the one we created. That a game gets finished at all is a feat in itself,

but another when it is effective, clear, and impactful. We got a small taste of

what it would be like working collaboratively on a team where the theme has

unique meaning to us, let alone our three different conceptions of how to make

it come alive.

Calvin: As

Isabella stated above, this process thoroughly enhanced my appreciation and

deepened my respect for the work of game designers. Accounting for the choices

and emotions of the player can seem like an endless assessment of variables.

Doing this in collaboration with other individuals who hold their own ideas,

visions, and methods of working can be daunting. As someone who struggles to

let go of his ideas, I was immensely grateful to be pushed by my teammates to

test, adapt, test again, and tweak our game into something we could all play

and enjoy.

Charming Offering can be played here

Participating in the GameBling Jam 2.0:

An Introduction to Game

Writing and Interdisciplinary Thinking

Alejandra Jimenez

On

February 11–12, 2023, Concordia University’s Technoculture, Art and Games (TAG)

and the Jeu Responsable à l’Ère Numérique (JREN) hosted the GameBling Jam

2.0. The goal of this 48-hour game jam was to design and prototype a video

game around the theme (Un)Lucky! This article will dive into the experience of

participating in it and the framework to develop the game Cat Luck,

followed by a reflection on creative writing and interdisciplinary thinking

around the question: How does this experience produce new knowledge for

non-experienced participants in the field?

The

process of the game jam was captivating from the beginning, with tools to help

participants connect with each other, like the Discord channels where everyone

would introduce themselves, gather resources, get updates and announcements,

and easily reach out to mentors. This was an effective manner of enticing

contributors. On the first day of the jam, the opening ceremony took place in a

virtual room in the Gather app. Participants chose an avatar and a place to sit

around to set up teams and brainstorm ideas. Many of them were experienced

gamers, programmers, designers, and creators. This was a scary scenario for a

firstcomer. However, the feeling was quickly dissipated by the collaborative

environment in which the groups were well-balanced to develop ideas

efficiently.

For

someone who has spent a long time without frequenting video games other than

those easy, non-thinking, addictive cooking Android video games or those

memories in the back of their head such as Atari or 8-bit games, the idea of

the GameBling Jam brought some questions regarding the skills needed to

participate. Having a background in acting and theatre, I reflected on the

contributions of interdisciplinary thinking regarding creative writing for

video games, storytelling, and visual representation. Does drama theory have

anything to do with video games? How are the connections built between the

story, the goals, the obstacles, and the player? How would the story

information be displayed without generating a dialogue-based game?

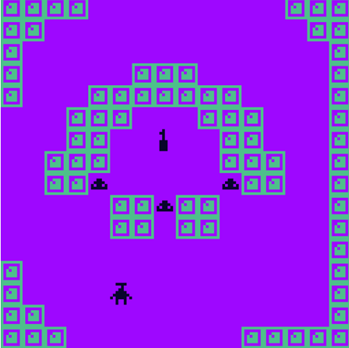

Cat Luck

Cat

Luck (Jimenez & Isdrake, 2023) was a collaborative

game developed for the GameBling Jam 2.0 using Bitsy by Alejandra

Jimenez and Idun Isdrake. It aims to achieve a basic idea: a fiction about

success and fortuity. It was a compelling process that explored universal,

shared beliefs and codes related to luck. The main character is a cat who plays

in a punk band and is trying to get to play on stage while surviving in the

brutal world of artists. Greta, the cat, is helped by a witch, the player. The

witch’s luck will be challenged by a series of jobs, problems to solve, and

fortuitous events to get the cat to the concert.

The

diegetic world created for this game was based on events that happened to close

friends or to ourselves, or in fictional situations where a punk cat could get

involved. During the brainstorming for the game design, one of the team’s

insights was that luck is related to success. Cat Luck is a parody of

the challenges behind the art world. Also, the group discussed the dichotomy of

good / bad luck, superstition, and the imaginary that might vary

culturally. The game would bring the player into scenarios meant to struggle

with misfortune.

This

helped define some obstacles, characters, and rooms following the premise of

keeping the game simple with a clear set of tasks to solve. There are ten rooms

in total. In each one, the cat shapeshifts, and there are obstacles for the

player to access more rooms.

The

video game aesthetics are based on the 1980s–1990s. The experience of using

Bitsy to create Cat Luck brought the spirit of that time. Although it is

a user-friendly engine, one of the challenges was the time constraints.

Composing with blocks, a two-dimensional image became difficult due to the

number of rooms. Nevertheless, it was clear that a visual reference with

minimal elements would display a sense of space concerning the script. Cat

Luck has a fair result despite the difficulties of getting more elaborate

scenarios. More questions related to writing and game design emerged by

developing this game. Is there a level of detailed descriptions of time and

space present when writing the story that can be suppressed when drawing? If

so, what other ways are possible to integrate them?

Writing the (Un)lucky

The

GameBling Jam 1.0 studied the relationship between gambling and slot

machines. In the article titled “The GameBling Game Jam: Game Jams as a Method

for Studying Gambling Games,” posted in the Critical Gambling Studies Blog,

Hoebanx et al. (2023) refer to game jamming as an innovative procedure of

exploration to inquire and build on concepts related to social science. The

theme “(Un)lucky” in the 2.0 edition was fundamental because of its relation to

gambling. Thus, by understanding luck as a mere chance or a ritualistic

behaviour independent of the set of skills that a player or a game might have,

there is an occasion to inquire about the perception and control of the

cognitive outlook that game designers apply to gamble.

The

theme “(Un)lucky” is recurrent with several references. The following two, a

video game and an animated film, show a contrast in how it is presented.

Although these weren’t considered for the game development during the jamming,

they will help to analyze and open up some elements of creative writing. When

communicating a topic, emotions are also evoked. In any form of storytelling

(including theatre, literature, graphic novels, movies, and video games), the

story is organized around a narrative structure so that the theme communicates

a meaning and a message. It attempts to engage audiences and readers

emotionally.

In

2017, the video game Night in the Woods was launched by Infinite Fall.

This is the story of Mae Borowski, a cat returning home to reconnect with the

life she left behind. However, things are different, and the woods seem strange

when the night arrives. The character-driven adventure game creates a world of

exploration with a successful story. Moreover, it discusses complex themes with

a good sense of humour and eerie places. The player has the chance to choose

the dialogues affecting some interactions. Mae is a character constantly taking

risks and getting involved in dangerous situations, some of them near-death

experiences.

Nevertheless,

the cat is lucky and smart enough to unexpectedly discover a mystery and accept

the changes in her life. In a review posted on the IGN YouTube channel, Chloi

Rad (2018) finds that “mystery adds some dramatic impetus” due to the

interactions between each character’s journey becoming vital for the story. Night

in the Woods is a single-player game in which they are engaged with the

characters and the narrative because their decisions affect the story.

The

2022 computer-animated movie Luck, directed by Peggy Holmes and Javier

Abad, portrays an optimistic moral tale around the human concept of luck. The

plot is set in the Land of Luck, where Sam Greenfield, an unlucky person, finds

a black cat named Bob. They join together in a journey to turn Sam’s luck back.

Elements like the penny, portals, clovers, leprechauns, and stones are present

during the film. Good chance is the main character’s goal. However, they get

involved in clumsy, unlucky situations and life events while traveling across

the Earth, the Bad Luck Land, and the In-Between. Characters like a dragon and

a unicorn manage those places. During the journey, Sam understands that things

aren’t fixed, that humans need to try hard in life, and that it is possible to

see some good luck in bad situations. According to a review posted on YouTube

by CinemaSins (2023), excessive deployment of symbols about good chance makes

the film predictable and naive.

In

the videogame version, elements of superstition are displayed within

well-structured and plausible situations. This creates an environment for the

player’s engagement by building out their own backstories and shaping the main

character’s life. In contrast, the animated film aims to catch the viewer’s

morals optimistically. The story’s situations are evidently life’s clumsiness

instead of unlucky ones. Everything is set up, so the emotional arc ends with

an optimistic and ingenuous message. Luck is a goal; it’s an ending point. A

single space for the viewer to engage differently with the topic is unlikely to

happen. It might seem unfair to compare two unique languages. Regardless, this

comparison informs how these stories related to luck are presented in different

media with dissimilar goals.

On

the one hand, the opportunity to intervene in the story with the player’s

choices; on the other, the message that human incompetence is a product of bad

luck. Looking deeper into those narratives, is the perception of luck /

chance fixed in our belief system, or is it induced and controlled?

To

develop that inquiry, first, it is relevant to provide some information on what

writing for video games means and if there is a relationship with traditional

writing. Later, it will be necessary to include an analysis through the lens of

interdisciplinary thinking.

In

the article “Explainer: The Art of Video Game Writing,” posted in The

Conversation, Maggs (2016) mentions that the narrative is all that is

built, it is the wholeness of the game and “it can be informed by art, gameplay

design and technical capability that already exist.” Adjustable storytelling

would be central to developing those other clue elements: the game world or the

tactics. It will help to plan the narrative and the game’s progression.

Although game writing can be supported by traditional narrative, it is

different due to the many aspects involved in the design and development of

digital games.

To

continue building on some comparisons between these two writing styles, in the

video blog Game Writer’s Corner, Kae (2020) highlights some of the

differences and challenges of moving from writing more conventional works,

novels for instance, to writing for digital games. She explains that the

narrative is only one part of a more complex production: “Most people will not

care about the dialogue, most people will not remember the characters, most

people will not bother to read the lore” (1:15–1:23). This is related to the

types of players that are involved in the game industry: The Narrative Kindred

Spirit, who is going to be wholly engaged with the story; and The Ludologist,

whose only interest is to play the game. In this regard, no story, dialogues,

or characters are needed; the gameplay would have a clear standpoint; and the

information (quest cues and objectives) would be short, clear, and concise so

that the player’s time is respected. Also, she suggests that dialogues are not

the only way to display information. However, the writer would cherish both

types of players. Hence, this informs how writing for video games is part of a

whole environment where designers tell stories visually, and not everything

relies only on the written word.

Interdisciplinary Thinking

The

experience of participating in the GameBling Jam 2.0 was nourishing and

provided a creative outcome and research possibilities as well. Some insights

are related to the levels of development of each of the video games, how teams

are constituted, the level of expertise using the engines, and the time provided

for the game jam. In prototypes like Cat Luck, interdisciplinary and

collaborative perspectives led to exploring and integrating interests in both

digital games and theatre.

According

to Hoebanx et al. (2023), a game jam is a way to “help new research interests

emerge through the process of game creation.” This statement raised questions

related to my discipline and the game development to expand on in writing. What

tools are required to tell a story in video games? What are the links between

metauniverses, for instance, between a play and a video game, that expand the

audience’s / players’ experience? What makes a video game engaging for

players? Is it the story or challenges, the characters and their goals, the

difficulty levels, or the narratives?

Theatre and Video Games: A Revision of Paradigms

The

relationship between theatre and video games can be traced by comparative

drama. I will use the “soft game” theory to do so. Drama Theory is a

plurimedial form of structuring situations, conflicts, and actions in social

and theatre studies. Moreover, looking into this theory and the theme of luck,

the inquiry would be about the spaces that video game writing opens to chance.

Does interactivity depend on the narrative? How does choice work in

video games?

To

answer these questions, explaining the links and differences between video

games and theatre is necessary. Before that, it must be considered that digital

games are often understood as narrative media, which, like traditional media,

are based on representation. However, some argue that video games are based on

a different paradigm: simulation.

First,

Drama Theory is close to Dramatic Theory, which is specific to theatre

and drama studies. In the classic Western tradition, representation works to

explain and understand reality. Narrative and Drama are concrete manners of

representation. Drama creates a sensory impression for the viewers during a

performance. It is representational and based on a written text. It is a form

of literature in which conflict is the structure; it is the vertebrae. Conflict

produces tension, urgency, and motivation, usually due to the uncertainty of

its results. However, Drama is a plurimedial form of art that cannot be fully

understood with reference to the text itself.

Second,

Drama Theory is a problem-solving, analytical theory; an operational research

method based on Game Theory and building on metagame analysis. Howard (1994)

uses the concept of “soft game” theory to explore the transformations of a game

and how it may vary as a result of pre-play negotiations between players. These

negotiations involve “emotional persuasion and rational argument” (p. 187).

Thus, soft game theory contributes to identifying the transformations affected

by the inner dynamics of pre-play negotiations. In real-life situations, these

transformations come from people’s (or the player’s) perception of reality by

describing “rational and irrational processes of human development” (p. 187).

Howard (1994) based his studies on real-life games as much as on drama because

of its role-playing principle. He states: “Drama, like game playing, is, in

part, a rehearsal for real life and throws light on it in crucial ways” (p. 188).

Drama Theory concentrates on rationality, which conducts goal-directed

behaviour, creative transformations, choices, and decision-making based on

emotions and interactions.

Conversely,

there is an alternative to narrative and representation: simulation. Video

games are particular ways of structuring a simulation. According to Frasca

(2004), simulation models a new system based on a source, keeping some elements

and behaviours of the original in it. Thus, video games can express messages

that representation cannot, and vice-versa. Frasca explains that the narrative

paradigm and the storytelling model are “not only inaccurate but also they

limit our understanding of the medium and our ability to create more compelling

games” (p. 221). Although these paradigms have many elements in common,

their mechanics are different, and they have “diverse rhetoric possibilities”

(p. 222), where simulation operates as an “alternative semiotical

structure.”

Those

elements are core: characters, settings, and events. As per representation, the

narrative is a mechanism of structuring cognitive structures in rational

thought: it produces a description of circumstances and a sequence of incidents

that might be surpassed to generate a “solution concept”: a dramatic resolution

and a rational solution (Howard, 1994, p. 189). In simulation, more

compounded systems work as cogwheels where there is a “sequence of signs that

behave like machines or sign-generators” (Frasca, 2004, p. 223). It helps

to predict complex situations and behaviours by retaining their characteristics

and modelling them according to a set of conditions, which means that there is

a configuration of loaded particulars that generate reactions to certain

stimuli. According to Frasca, simulations are restrained, and diverse

approaches and rules exist to accomplish goals. He states: “In the realm of

simulation, things are more complex: it is about which rules are included in

the model and how they are implemented” (p. 231).

Evidently,

the contrast between these two paradigms is controversial. It has several

detractors and advocates divided into two positions: the narratologists

(or narrativists as named by Frasca) and the ludologists. The former

stand for video games as a new narrative, whereas the latter consider them in

their own nature: simulation. The narrative is binary in essence; it works in a

relation of cause and effect, while simulation does not require coherent

sequence, and yet, it can work with new starting points any time one plays it.

While in video games, the user can make choices, in a film or a book, an

observer can interpret the events rather than influence or manipulate them as

they are pre-established.

According

to Frasca (2004), “To an external observer, the sequence of signs produced by a

film or a simulation can look exactly the same” (p. 224) due to the

“well-lubricated tool” (p. 226) that narrative rhetoric establishes.

Although he addresses that it might take several generations to shift the

paradigm, interesting “cognitive consequences” might arise by changing the

“literary mind” to the “simulational way of thinking” (p. 224), which

means that an environment of experimentation and repetition is expected rather

than simply telling a story. However, such ideas sound very similar to Howard’s

drama theory. This approach to role-playing activities analyzes how human

processes such as values systems and perception of reality can change and

develop during a game that, to solve a problem, can exceed the rational

(reaching irrational emotional states), exhaustion of emotions, and creative

impulses to get a dramatic resolution, yet, rationally accepted. That is to say

that role-play approaches incorporate “complexity and emotion into a

simulation” (Bolton, 2002, p. 353).

Are there Convergences between Theatre and Video Games?

Games

have a system of participation rules with a clear goal, whereas spectators in

theatre are conceived as passive. However, theatre has transformed so much over

time. Over centuries, the misconception that theatre is “available only to the

eyes and ears” (Laurel, 2014, p. 60) implies that it cannot exist without

spectators.

Due

to the relationship between the stage (space), actors (players), and audiences,

the ritual (considering its antiquity and inherent development of

humanity) called theatre is created. Although there is a stimulation of the

predominant senses, there is a kinesthetic experience in the observer due to

the response of the mirror neurons. Thus, this idea about passiveness needs to

be more accurate. Conventional theatre is based on verisimilitude, which

is related to reality. As mentioned above, drama is the basis of

theatre, stimulating the spectators’ senses to impact them emotionally. In this

paradigm, theatre creates the illusion that everything happening on stage is a

reproduction of reality.

In

contrast to the Aristotelian principle of theatre as an illusion, theatre as

theatre was developed by, among others, by Bertolt Brecht, Vsévolod

Meyerhold, and more contemporary theatre directors like Augusto Boal. The

illusion of theatre neutralized the spectators’ present reality, impeding

social changes. It is relevant to say that theatre was an essential way of

entertainment, and because of that, reality was presented as an “inexorable

progression of incidents without room for alterations” (Frasca, 2004, p. 228).

Theatre as theatre is a principle in which the spectator is aware of the use of

effects to create theatricality and, instead, has a rational response to the

facts presented on stage. The tension of principles between the paradigm shift

from dramatic to post-dramatic theatre involved relational, participative, and

interactive forms. Theatre in the 1960s and 1970s had experimental perspectives

that focused even more on impacting other senses, engaging audiences with no

conventional dramatic conflicts, non-linear stories, and breaking the barriers

of representation. This also gave birth to performance art.

It

is often thought that theatre has nothing to do with digital games, and they

might seem contradictory. However, this comparison has also had several

advocates and detractors, as described before. Nevertheless, those statements,

nowadays, are problematic due to the borders vanishing between both paradigms

when referring to interactivity. In the book Computers as Theatre,

Brenda Laurel (2014) established the vast similarities between video games and

theatre, contributing to the idea of interactive narrative.

Theatre,

like cinema and TV, has been used as a reference to create video games due to

how tension and uncertainty are presented. The traditional narrative

(Aristotelian) follows a three-act structure: presentation–conflict–solution.

This creates a dramatic arc in which the events are processed in

tension, climax, and resolution. For instance, adventure games (role-play and

strategy games as well) follow the conventional structure of the “hero (or

anti-hero) journey.” This system presents a character (created with several

characteristics and features to generate engagement) who, in general,

faces a moral dilemma that must be solved according to established and

normative morals. Howard (1994) indicated the term “paradoxes of rationality”

to explain six dilemmas generated by a rational approach to conflict (p. 189).

As described before, in theatre, players are actors, and spectators only

observe actions; whereas, in video games, players are both characters and

spectators.

Frasca

(2004) references Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed to give an example of how the

simulation rhetoric creates an environment for education and reenactment. In

this theatre technique, called Forum Theatre, Frasca sees a theatre of

simulation: an oppressive system (reality) is modelled by a representation

system (the play). While issues are presented, the play can be interrupted to

integrate a person from the audience to improvise, take the leading role, and

change the story, giving a possible solution. The plot was created

collectively, and the spectators were also meant to be actors. Boal called them

espectactor. This is a virtuous manner of participatory theatre close to

the video game simulation rhetorics with a different approach from the

conventional narratives. This idea joins both roles of a video game player: an

actor who jumps into the story and a spectator of their actions. In Boalian

drama, what’s interesting is the fact that the simulation is set by a

non-digital, virtual, or computer-based domain that generates a captivating

involvement in the play and a level of autonomy to be part of it. The feature of

interruption and modification of the story is closer to gaming. In the idea of

modification, an espectactor reaches their goal: go along with the imagination

and adapt the game to diverse changes.

Essentially,

what Frasca is conveying is the need to get rid of the “narrative coherence,”

which is well defended by Laurel in the interactive narrative, arguing the

“Aristotelian closure as the source of the user’s pleasure” (2014, p. 229).

On the other hand, Frasca (2004) remarked that the potential of games is the

player’s capacity to start over and enhance their knowledge through the

interpretation of simulated experiences and their repetition. Hence, for a

digital game player (or an espectactor), what is compelling is the make-believe

rather than the closure.

Insights on the “Make-Believe”

The

categorization proposed by Roger Caillois (2001) in game studies can frame the

essence of theatre as mimicry or mimesis, which is role playing.

Caillois establishes three more categories: Agon or competition games; Alea

or chance games; and Ilinx or vertigo games, in which perception is

altered. This classification defines four play forms that continuously

intersect. Two types are structured in a broader spectrum of these categories

and are framed by the play continuum: ludus and paidia, play and

game. One follows a well-defined structure and a set of rules, with winners and

losers. The other is spontaneous, and the rules, although structured, can be

more abstract. Ludus games are more linear and binary, while paidia are more

“open-ended” (Frasca, 2004, p. 230).

From

the acting point of view, as a performer and an actor, I learned that acting

is playing. That rule is applied almost everywhere and taught in every

corner of drama and theatre schools. In English, “play” has diverse meanings,

being a noun and a verb. So, theatre across time has been defined by various

philosophical concepts, and the first is the Aristotelian one of mimesis:

imitation. It is how the actions and events of the characters are shown instead

of being told by a narrator (diegesis). Mimesis is an essential human

feature that involves observation and repetition; in this way, children learn

to behave. Hence, as an actress, my relationship with theatre begins with that

primarily human behaviour. Also, it is undeniable that theatre has taken

centuries to analyze and develop accurate techniques (for playwrights and

actors) to create characters that engage the audiences.

Moreover,

every theatre style has a basis in the make-believe principle. I have also been

an espectactor, a practitioner of the Boalian theatre, Stanislavksi’s method,

Brechtian distancing effect, and Meyerhold and Grotowski’s technique, where the

body and objects (kinesthetics) are the first links between reality and the

simulation of it in worlds modelled by playwrights, dramaturgs, and stage

designers. I have practiced performance art where no acting is needed except

the mere presence in a real-time space doing an action. Here, the relational

sphere with others nourishes the work. As an espectator, I have also

participated in participatory and interactive theatre. Thus, whether inside or

outside the theatre or video games, a player’s experience is kinesthetic,

cognitive, and emotional; if winning or losing is involved, the engagement

would change accordingly.

Theatre

and technology have blurred their borders, serving one another as models.

During the 1980s and 1990s, conventional narratives influenced the design of

video games, and now, digital games and interactive technologies are more

incorporated in theatre pieces worldwide. Nowadays, audiences take up more

space, becoming players, who are, at the same time, playwrights, actors, and

directors. In regard to digital games, simulation appears as an “alternative”

rather than a “replacement” of representation (Frasca, 2004, p. 233)

because their difference goes only to a certain point. On the other hand, Homan

and Homan (2014) stated: “It may be that the video game … will, we think,

become a (rather than the) theatre of the future, or at least the most popular

new expression of theatre’s evolution” (p. 184).

Conclusion

Participating

in TAG and events like the game jam can contribute to producing research

questions and interdisciplinary methods for creators, gamers, and non-gamers.

It made me rethink my practice because it expanded my information and skills.

This is also a way to understand the game design’s collaborative, technical,

and iterative aspects. It was also an encouraging laboratory of creative

writing and its expansions to interactive theatre. Thus, new knowledge is

acquired.

Earlier

in this essay, I referred to the GameBling 2.0 regarding the topic

(Un)Lucky and the insights about game writing and its relationship to chance.

After examining multiple perspectives, I considered the question of whether

chance / luck can be modelled by changing the paradigms in which it is

framed. Considering perspectives such as Frasca’s ideas about the rhetorics of

simulation being a fundamental characteristic of digital games in contrast to

the narrative paradigm’s construction of a black-and-white experience, will

games written under the simulation rules shift the perception of luck on

players?

The

concept of paidia contributes to simulation rhetorics because it helps

establish diverse levels for the players to develop their own goals. Likewise,

simulations can be controlled to transmit ideology. Hence, luck and chance

could be manipulated in the writing and design process. Often, digital games

are perceived as spaces where skills are essential and can be enhanced by

practice and repetition. Also, they can develop tactical thought and,

therefore, success. However, further research is needed to address the

intersections of gambling and video games, supported by both game and gambling

studies, and applying methods such as game jams.

Alejandra

Jimenez is an interdisciplinary artist

and educator, developing her Ph.D. studies in Humanities in the Individualized

program at Concordia University. She holds a B.A. in performing arts from

District University-ASAB and an M.A. in theatre and live arts from the National

University of Colombia. She is interested in creative, transformative, and

communal experiences that address critical intersectional concerns. Alejandra

is a Teesri Duniya Theatre board member, and an editor and workshop facilitator

at Kodama Cartonera. She is affiliated with Hexagram, Milieux-LeParc, COHDS,

ALLab, and SenseLab-3e at Concordia University. https://www.alemisakg.com

Works Cited

Bolton, G. E. (2002). Game theory’s role in

role-playing. International Journal of Forecasting, 18(3), 353–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2070(02)00027-4

Caillois, R. (2001). Man, play and games (M.

Barash, Trans.). University of Illinois Press. (Original work published 1958) https://www.press.uillinois.edu/books/?id=p070334

CinemaSins. (2023, June 22). Everything wrong

with Luck in 23 minutes or less [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IPgaSgzm7PE

Frasca, G. (2004). Simulation versus narrative:

Introduction to ludology. In M. J. P. Wolf & B. Perron (Eds.), The video

game theory reader (pp. 221–236). Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/The-Video-Game-Theory-Reader/Wolf-Perron/p/book/9780415965798

Hoebanx, P., Isdrake, I., Kairouz, S., Simon, B.,

& French, M. (2023). The GameBling Game Jam: Game jams as a method for

studying gambling games. Critical Gambling Studies Blog. https://doi.org/10.29173/cgs160

Holmes, P., & Abad, J. (Directors). (2022). Luck

[Film]. Skydance Animation.

Homan, D., & Homan, S. (2014). The interactive

theater of video games: The gamer as playwright, director, and actor. Comparative

Drama, 48(1/2), 169–186. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24615358

Howard, N. (1994). Drama theory and its relation to

game theory. Part 1: Dramatic resolution vs. rational solution. Group

Decision and Negotiation, 3, 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01384354

Infinite Fall. (2017). Night in the woods

[Video game]. Finji. http://www.nightinthewoods.com

Jimenez, A., & Isdrake, I. (2023). Cat luck

[Video Game]. itch.io. https://affectionsandmoves.itch.io/cat-luck

Kae, A. (2020, August 1). Game Writers’ Corner

|| Writing for video games: Why it’s different from other industries

[Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GXUrWtGZH3s

Laurel, B. (2014). Computers as theatre (2nd

ed.). Addison-Wesley.

Maggs, B. (2016, June 20). Explainer: The art of

video game writing. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/explainer-the-art-of-video-game-writing-60376

Rad, C. [IGN]. (2018). Night in the woods review

[Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SJXP99zwQQw

Further Readings

Beumers, B. (2000, October 27). Theatre as

simulation, or the virtual overcoat: Towards a theater of the postmodern.

ARTMargins. https://artmargins.com/theater-as-simulation-or-the-virtual-overcoat-towards-a-theater-of-the-postmodern

Bryant, J. (2021). From game theory to drama

theory. In D. M. Kilgour & C. Eden (Eds.), Handbook of group decision

and negotiation (pp. 485–504). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49629-6_14

Isigan, A. (2011, August 15). Urgency in video

games. Game Developer. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/design/urgency-in-video-games

Johnson, M. R., & Brock, T. (2019, January 21).

How are video games and gambling converging? Gambling Research Exchange

Ontario. https://www.greo.ca/Modules/EvidenceCentre/Details/how-are-video-games-and-gambling-converging

Mambrol, N. (2020, November 12). Drama theory. Literary

theory and criticism. https://literariness.org/2020/11/12/drama-theory

Manero Iglesias, B. (2015). Del teatro clásico a

los videojuegos educativos [Tesis Doctoral, Universidad Complutense de

Madrid]. Docta Complutense. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14352/26589

Technoculture, Art and Games (TAG). (n.d.).

Retrieved June 18, 2024, from https://tag.hexagram.ca

Wolf, M. J. P., & Perron, B. (Eds.). (2004). The

video game theory reader. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203700457

GameBling Jam Writing Workshop:

Flip a Coin Reflection

Vinh Tuan Dat (Percy) Nguyen*

*Concordia

University

Introduction

For

the GameBling 2.0 Game Jam, I made Flip a Coin: a simple browser

game where players bet money on one side of a flipping coin. The goal is

simple: gamble to your heart’s content and cash in the goods! The odds seem

reasonable to the untrained eye, as a 50% chance of winning is high in

gambling.

In

the (eventual) case of bankruptcy, players will be introduced to Russian

Roulette, a dangerous way to earn free coins. Whenever out of cash, players may

then risk their life to continue feeding their crippling gambling obsession.

Thought Process

I

was the sole creator on this project. In the initial stages of planning the

game, I envisioned a story-branching narrative game. I decided against this

because the random nature of luck removes the meaning of choices. In an

action–adventure game, players should be rewarded for making the right choices.

If player decisions are constantly influenced by random number generators

(RNG), winning is no longer gratifying, while losing feels empty and unfair.

Yet, this randomness is often the reality in commercial gambling where luck, or

rather bad luck, is a significant determinant that dictates gambling outcomes.

The

only choice that players can take in Flip a Coin is the simple action of

gambling. Players must comply with this act as it is their only option to

advance the narrative. The lack of player agency, bound to the repetitive act

of gambling, paints my vision of compulsive gambling and its momentous repercussions

for the gambler. This art of persuasion is called procedural rhetoric in which

the message of the game is conveyed through processes and rules-based systems.

By limiting players’ choices to one single path, or one recurring process, the

game mirrors the unyielding urge to gamble that addicted gamblers experience.

I

am quite content with the final game output. If given more time and skills to

develop this prototype, I would stray away from the theme of gambling and delve

into how people perceive luckiness upon birth. What factors decide a fortunate

upbringing? A solid country of birth or good wealth? A lack of birth defects or

happy, married parents? Luck is subjective and respective to each individual

and their worldview.

Reflections

As

a skeptical individual, I believe in cause and consequence rather than the

unpredictability of luck. I tend to lessen the importance of luck, being the

unexpected and the unaccounted factor, in favour of a predictable outcome. This

could be something like simply refusing to buy lottery scratchers to avoiding

driving late at night when the probability of accidents caused by driving under

the influence is the highest. While I understand that some factors are beyond

my control, I do have the choice to engage or disengage from dubious

behaviours. I dislike luck for how its unpredictability interferes with our

daily lives.

The

theme of luck and chance is implicitly communicated through the gambling

activities that players engage with. Betting with one’s money in a game of

heads or tails or wagering one’s life in Russian Roulette demonstrates the many

ways players try to beat the odds, regardless of potential consequence.

Flip

a Coin also explores the theme of

“beginner’s luck”: a superstitious phenomenon where novice players are believed

to experience early successes in gambling activities. New players are given a

ratio of 70% against 30% in Heads or Tails for their first five days. This

secret algorithm is employed to increase newcomers’ luck and invite them to

indulge in gambling. However, from day five onward, the win / lose ratio

is altered to 45% versus 55%, subtly reducing players’ win rate to ensure

profit for the casino. Given that the odds are against players, bankruptcy is

meant to occur with time, forcing players to resort to Russian Roulette.

Russian Roulette has odds of 5 to 6 for a chance of winning a thousand dollars.

However, losing only once will result in death, or rather, an immediate game

over.

Original Intention

Flip

a Coin is a ridiculous and satirical

take on gambling games. The game takes a critical and humorous stance as it

punishes players with a virtual demise for their gambling endeavours. As the

game progresses, a new twist emerges: from the tenth day onward, the game

forces players to wager a higher amount than their previous bet in the Heads or

Tails minigame. This rule effectively trains players to adopt a high-risk,

high-reward approach. From risking bankruptcy to betting one’s very existence,

the stakes in play evolve over time to mirror a gambler’s growing greed. The

introduction of Russian Roulette as a means to address bankruptcy adds a poetic

and extreme layer to the gameplay. The chamber-spinning minigame is but a

poetic and extreme analogy of modern gambling machines, highlighting the irony

of risking one’s mortality for another shot at the thrill of gambling. It

exposes the disconnect of gamblers from reality and their compulsion to satisfy

an insatiable abyss of avarice.

Flip

a Coin communicates a narrative of

stress and suspense through sound design. The juxtaposition of the upbeat

casino jazz in Heads or Tails to the silently spinning cylinder of the Russian

Roulette revolver speaks volumes about the severity of the nature of gambling.

Critical Theorization

Marionneau

and Nikkinen (2022) note that suicidality increases amongst heavy gamblers as

opposed to their nongambling counterparts. Citing a past United Kingdom study

on gambling-related suicides and suicidality, the authors note that “19.2 percent

of problem gamblers had thought about suicide in the past year, in comparison

to 4.1 percent among those with no signs of problem gambling.” Similar

studies in Sweden and Italy also reveal an increase in suicidality amongst

problematic gamblers (Marionneau & Nikkinen, 2022). While the severity of

gambling is not directly linked to suicide, indebtedness and shame are bridging

processes that connect the two acts (Marionneau & Nikkinen, 2022).

Upon

reading this study, I realized that indebtedness and shame are two missing

factors that define the harms of gambling in Flip a Coin.

As

the player’s balance could never go below zero, this unrealistic game mechanic

takes away the anxiety-inducing debt that is present in heavy gamblers. Certain

forms of monetary punishments would serve as a great middle ground, a

transition from normal life to one of indebtedness and fear, forcing players to

resort to gambling their own life. Introducing new options to the game, such as

offering different types of loans, would help to ground this virtual game to

the actual world and present a much more realistic demonstration of gambling

problems.

Incorporating

shame into Flip a Coin would be another needed but difficult task as I

have not experienced first-hand compulsive gambling. It then would be best to

crowdsource data from past and present problem gamblers to depict this

heartfelt embarrassment from gambling problems.

Flip a Coin can be played here

Bibliography

Marionneau, V., & Nikkinen, J. (2022).

Gambling-related suicides and suicidality: A systematic review of qualitative

evidence. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 980303. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.980303

Game Credits

Art

Glass: https://www.pngwing.com/en/free-png-bmteg/download

Kawaii face: http://clipart-library.com/clip-art/kawaii-face-transparent-background-5.htm

Russian Roulette: https://depositphotos.com/vector-images/russian-roulette.html

Sounds

CasinoBG Music: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=99ABAddEiQs&ab_channel=MelodySounds-CopyrightFreeMusic

Cocking Revolver: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bZPUqxZRiLQ&ab_channel=TMGOTBEATZ

Coin spin: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7c0xKlRkFlw&ab_channel=SoundEffectsLibrary

Pick sfx: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=shI-BL0y8Kg&ab_channel=Jocabundus

Revolver Click: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Potg0kDqIXc&ab_channel=FreeifyMusic

Revolver Spinning: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hjZElXeXgQU&ab_channel=PSSoundeffectsFX-NoCopyright

Shooting SFX: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qgB3fY0Amhs&ab_channel=ScottRoman

Comments

Post a Comment