‘Gotta catch em all!’ The Gaming/Gambling Dynamics of Pokémon TCG Pocket

Matthew Fitzpatricka

aUniversity of Birmingham

This non-peer-reviewed entry is published as part of the Critical Gambling Studies Blog. To cite this blog post: Fitzpatrick, M. (2025). ‘Gotta catch em all!’ The Gaming/Gambling Dynamics of Pokémon TCG Pocket. Critical Gambling Studies Blog. https://doi.org/10.29173/cgs234

Introduction

Loot boxes in video games have attracted the attention of public health scholars in recent years due to continuing controversy regarding potential connections to problem gambling and mental health risks – although the latter is contested, with studies reporting conflicting results (Armitage, 2021; Wardle & Zendle 2021; Spicer, 2021; Xiao, 2024; Villalba-García, 2025). Regulators have also been paying attention to the loot box controversy; in the UK, both the House of Lords and former Children’s Commissioner for England have recommended that the Gambling Act 2005 be amended to incorporate loot boxes into the UK definition of gaming (Children’s Commissioner for England, 2019; House of Lords, 2020). Despite such controversy, loot boxes are generally not regulated as gambling in most jurisdictions, and in Belgium, the only country to incorporate a complete ban on loot boxes, the ban has been severely criticised for its poor implementation and enforcement (Xiao et al., 2022; Xiao et al., 2025).

On the 30th of October 2024, Nintendo released the latest game in their highly successful multimedia franchise Pokémon titled Pokémon Trading Card Game (TCG) Pocket. This game is a simplified, digital version of the physical Pokémon trading card game; trading card games (TCGs) are deck building chance and strategy games where players collect cards and can then use them to play with other people (Craddock, 2004). Since its release, the game has seen incredible success, having generated an estimated $500 million USD globally within just three months of release, making it the second most successful Pokémon mobile game behind Pokémon GO (Dinsdale, 2025a).

This blog seeks to explore the gaming/gambling dynamics of Pokémon TCG Pocket to contribute towards discussions regarding loot box regulation with a view towards advocating for a stricter public health approach to how jurisdictions tackle the issue of loot boxes (Close & Lloyd, 2021; Dixon & Larche, 2021; Xiao et al., 2022). Loot boxes have been the subject of significant controversy due to their similarities to gambling such as slot machines, having links to problem gambling, and the gaming industry’s ever-growing reliance upon them (Salmon, 2021; Kolandai-Matchett & Abbot, 2021). Pokémon is an extremely well-known and popular video game franchise, particularly with children and young people, which makes its hyper-aggressive monetisation strategy particularly worthy of focused analysis.

‘Collection’ and ‘Competition’ – Motivations of play:

There are ostensibly two identifiable ‘purposes’ for playing Pokémon TCG Pocket; the ‘card game’ itself and collecting the cards. Player behaviour, motivations, typologies, and traits form a complex topic, with numerous studies attempting to both understand and model differences in player motivations stretching back almost 30 years (Hamari & Tuunanen, 2014; Tondello, 2019; Diaz, 2022). An in-depth discussion of such studies goes beyond the scope of this blog, however. We will confine ourselves here to only two overarching categories/types of ‘motivations’ for playing the game, ‘collection’ and ‘competition’ and discuss these orientations accordingly. My reason for using motivations rather than the more abstract player ‘archetypes’ or ‘traits’ is due to the reductive nature of these metrics – player diversity means that players will be drawn to the game for a number of reasons which may overlap.

‘Collection’ refers to the card collection aspect of the game – enjoyment can be derived from collecting cards, seeing one’s collection grow, and possibly even comparing collections with friends and strangers alike; collection contains aspects of aesthetics, social, and goal orientation (Tondello, 2019). Competition refers to the card battling aspect of the game – this generally encompasses casual play against other players as well as play at a competitive level in official or community tournaments; competition contains aspects of goal, social, and challenge orientations (Tondello, 2019). The way that games appeal to motivations of play are not inherently negative, but they can feed into what are known as ‘dark patterns’ which are defined as “something that is deliberately added to a game to cause an unwanted negative experience for the player with a positive outcome for the game developer” (Dark Pattern Games, n.d). While it might sound oxymoronic for negative experiences to factor into motivations of play, this article will explore how some game mechanics draw parallels between motivations, game design elements, and dark patterns.

The Rules of the Game

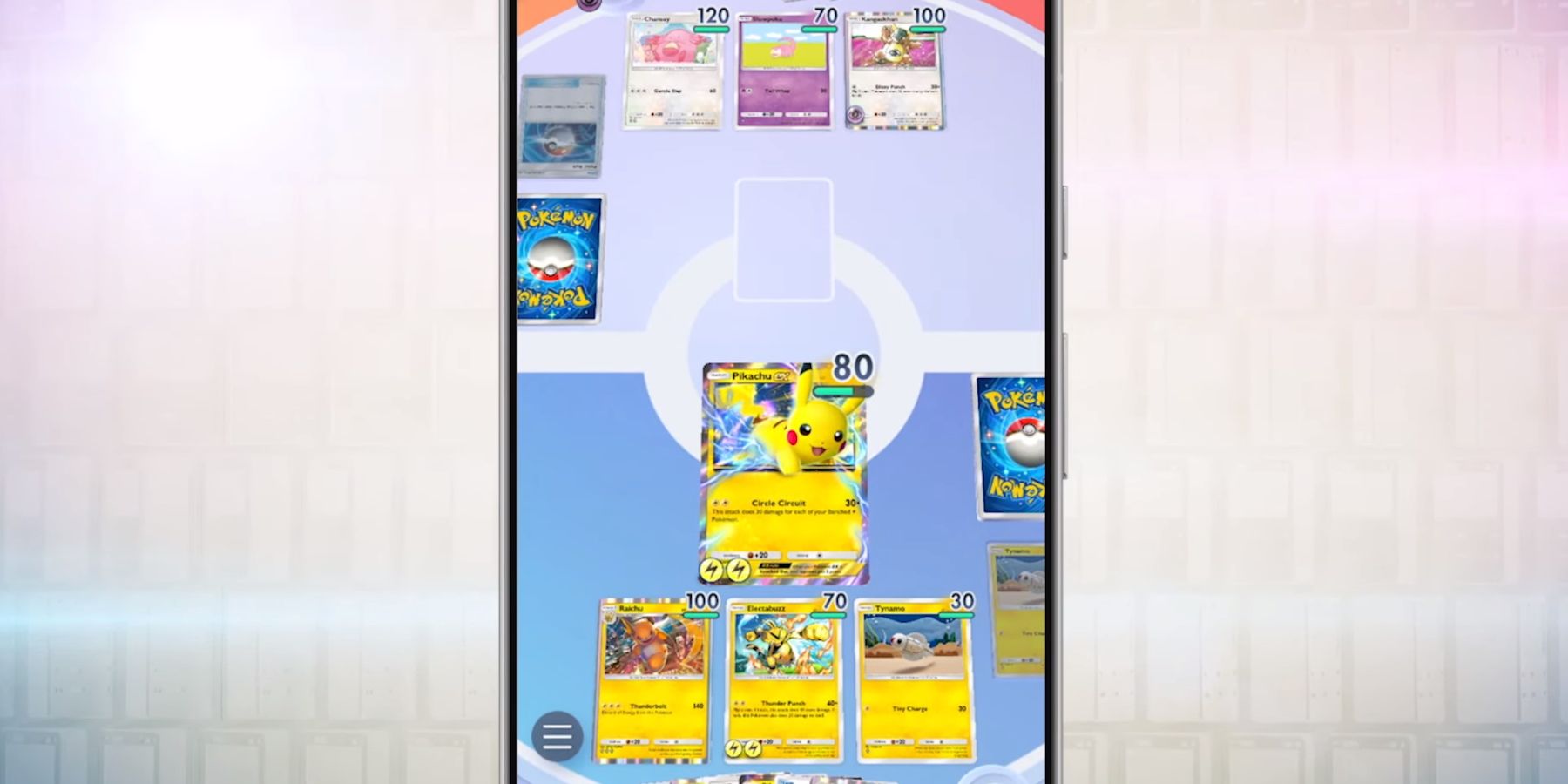

Ultimately, due to the game’s mechanics, both types of players will still need to battle to get the ‘full’ experience of collection and competition. Before I proceed with an examination of the loot box mechanics in Pokémon TCG Pocket, it is necessary to explain how the game itself is played to provide overarching context to the motivations for loot box play. In this game, each player starts with a hand of 5 cards from a deck of 20 cards, with player decks comprised of two different types of cards, trainer cards and Pokémon cards. Pokémon cards are the main cards in your deck and are necessary to play the game; a player’s game plan will typically revolve around one or several Pokémon and their abilities to win the game. Trainer cards support your Pokémon cards and can do various things such as accelerate your game plan by drawing or adding cards to your hand or disrupt your opponent by making it easier to defeat their Pokémon or harder to defeat yours.

The board is comprised of 3 zones, the ‘active spot’, the ‘bench’, and the ‘energy zone’; the active spot is where the player’s currently active Pokémon is, the bench has three zones and also contains Pokémon, and the energy zone is where the turn player’s energy is generated at the start of the turn – energy is used to fuel Pokémon’s attacks. The objective of the game is to either be the first player to get to 3 points, or to remove all of your opponent’s Pokémon from the active zone and the bench. Players receive 1 point for defeating an opponent’s Pokémon, or if that Pokémon is an EX Pokémon (stronger versions of Pokémon with more powerful attacks and abilities) the player gets 2 points to compensate for the EX Pokémon’s power. Players defeat a Pokémon by battling them, using attacks with different energy costs to attack their opponents active Pokémon to reduce their HP (hit points) to 0, thus ‘knocking out’ the active Pokémon and forcing them to replace it with a Pokémon on the bench. If the player has no Pokémon on the bench to replace their active Pokémon with, they lose the game.

|

| Figure 3. The Game Board, Baqery M, Gamerant, 2025 |

Rarity in Pokémon TCG Pocket

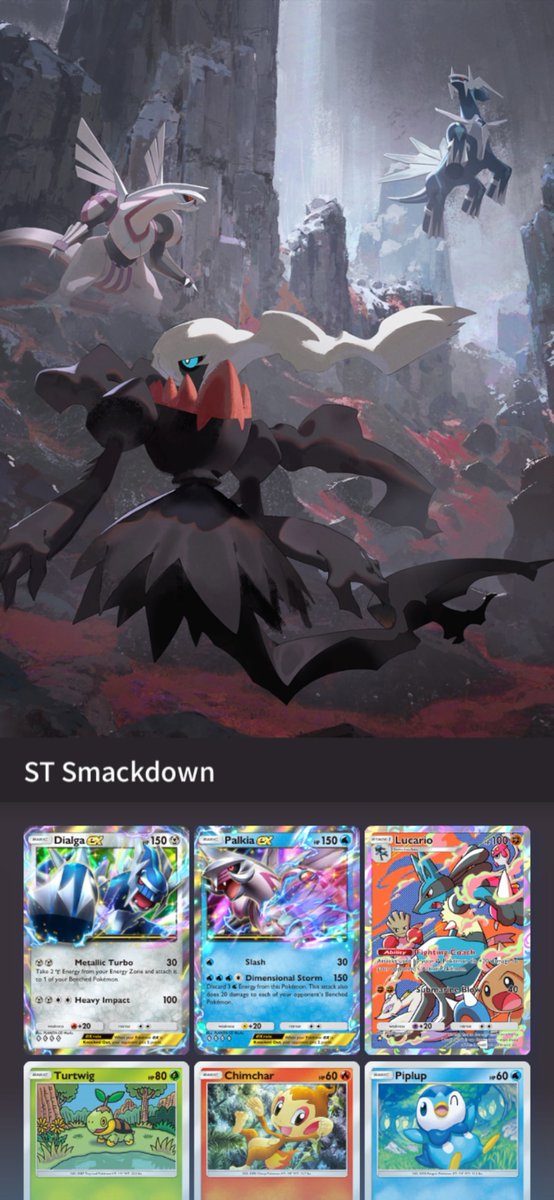

The main card collection method in Pokémon TCG Pocket is through the game’s loot boxes which take the form of virtual card packs. Similar to its physical counterpart, Pokémon TCG Pocket does not provide players with a complete collection at a point of sale; rather, they sell digital versions of “blind sealed packages of randomized cards of varying power and value” (Xiao, 2021). Conventional wisdom would dictate that the more powerful a card is, the rarer the card should be (Ham, 2010); this is reflected in Pokémon TCG Pocket through its complex 10-tier rarity system. The higher the rarity, the lower the probability of obtaining a card of that rarity; additionally, higher rarities contain more powerful cards such as EX Pokémon, as well as special versions of cards available at lower rarities. | Figure 4. Card Rarities, game8, 2025 |

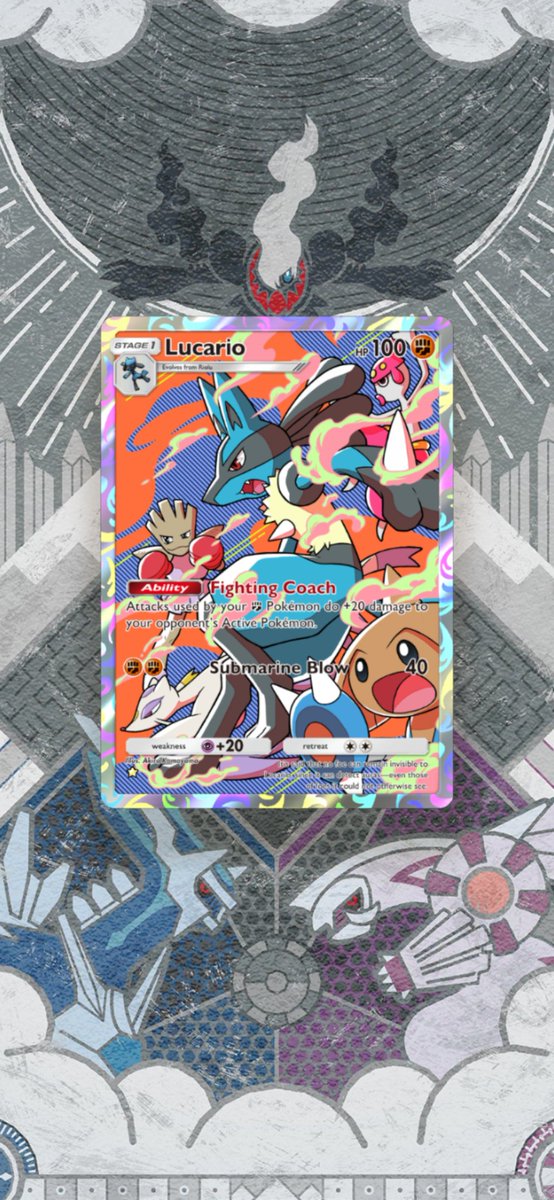

Binders and the display board encourage players to show off their favourite cards to others. It is an opportunity to demonstrate their engagement and social prestige within the game by showing off their rarest cards, most powerful cards, or any card they are particularly proud or fond of (see figures 5 and 6). While not the perfect analogy given how vastly different they are in terms of gameplay, comparisons can be drawn to the social motivations for advancement in MMO’s through symbols of wealth or status (Yee, 2006; Van Looy, 2010). The use of social spaces outside the game environment such as social media can also play a part in this motivation, with players wishing to show off their collections to as wide an audience as possible. This, in-turn, serves as positive advertisement for the game and may entice other players to become engaged with the game’s mechanics by stoking a sense of competition through collection.

|

|

Figures 5 & 6: Binder and Display Board, Serebii.net [@SerebiiNet], X, 2025 |

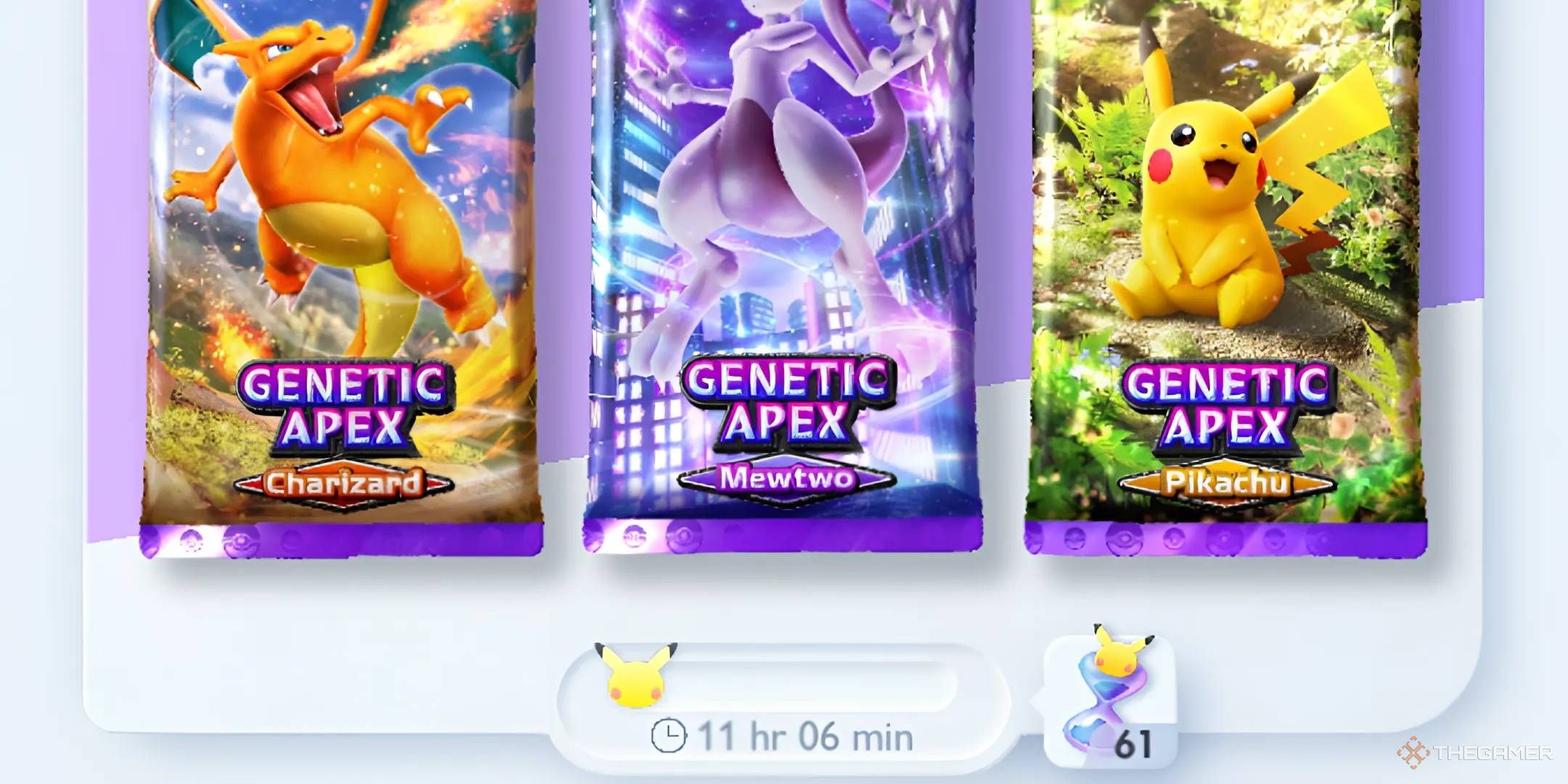

Timers – Monetizing Impatience

Card packs in Pokémon TCG Pocket belong to different expansions, with each expansion adding new cards to the game. Players can earn one pack for free every twelve hours up to two packs per day. Once the player has expended their two free packs, they must either wait twelve hours before they can open another pack, or use one of two in-game currencies, ‘Pack Hourglasses’ and ‘Poké Gold,’ to lower the timer. Hourglasses and Poké Gold can be earned in limited quantities during the regular course of play, but Poké Gold’ can also be purchased for real money inside the in-game shop.Timers are also used to influence players’ gaming habits by encouraging them to space out play throughout the course of a day to prevent burnout. This results in players spending more time with the app overall, leading to increased exposure to the game’s loot boxes and encouraging the development of a ‘habit of play’ (Dark Pattern Games, n.d.a). This is reinforced by the game’s use of daily rewards which create an “obligation to play” by capitalizing on a players fear of “missing out” if they do not login to the game daily (Frommel & Mandryk, 2022). These daily rewards take the form of ‘shop tickets’ which can then be used to buy Hourglasses from the in-game store, making them another (albeit indirect) method to reduce the loot box timer. Shop tickets can also be used to buy other items such as cosmetic accessories like binder covers and card sleeves, amongst other things, which further appeals to the social status aspects of collection as described above.

Confusing Design Elements – Price Obfuscation and Spending Limits.

The use of multiple in-game currencies, which can be used to buy other in-game currencies in some cases, can be confusing to players and makes it difficult for them to accurately determine the “true cost of in-game transactions” (Petrovskaya & Zendle, 2021). In addition, Poké Gold cannot be purchased individually, but rather in bundles at fixed purchase rates which give an incrementally better exchange rate as the bundles get larger (Petrovskaya & Zendle, 2021). For example, the minimum bundle of 5 Poké Gold is $0.99 USD, which equates to roughly $0.20 USD per unit. The largest bundle of 690 Poké Gold, however, has the “best” value proposition and converts to roughly $0.14 per unit, a $0.06 USD “discount” for each Poké Gold.‘Wonder Picks’ – Integrating Loot Boxes into Social Spaces of Play

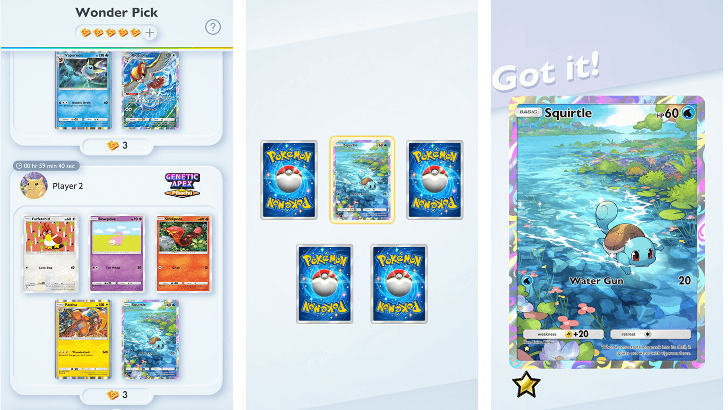

The virtual card packs are not the only loot boxes in Pokémon TCG Pocket – the game has an additional loot box mechanic called ‘Wonder Pick’, which allows players to pick a card at random from packs opened by their friends and other players (see figure 8). To use the Wonder Pick system, the player must spend ‘stamina’ which recharges at a rate of 1 stamina every 12 hours or by skipping the timer using in-game currency. The number of stamina used per Wonder Pick is determined by the highest rarity card in the pack that the player chooses, with higher rarity packs costing more stamina. Social systems in games which utilize friend mechanics are an established game mechanic, with free-to-play games commonly offering things such as sign-up bonuses to encourage people to get their friends to download the game. Poké Gold can also be used on Wonder Picks to gain more stamina and reduce the timer; however, a key difference between virtual packs and wonder picks is that the latter is only available for a limited amount of time before a different pool of cards is generated. Wonder Picks are also used for special time-sensitive in-game events, which offer a random chance to obtain cards that are unavailable through other means and may potentially not be offered again for months, or even years. The time-sensitive nature of these Wonder Picks may make players feel pressured into impulsive decision making out of fear of missing out on potentially valuable rewards that they may not get another chance to obtain.

Wonder Picks give players additional chances at obtaining cards from packs other players and their friends have pulled from to increase their card collection or empower their decks. This is an example of the social dark pattern of ‘reciprocity’ which is based upon a player’s sense of obligation to “return a favour” that is paid to them (Dark Pattern Games, n.d.a). In this case, Wonder Picking a card from a friend’s pack could incentivize a player to then pull packs to ‘return the favour’ and give their friends and other players additional chances to receive cards too. This creates a feedback loop of reciprocity – Player A pulls from a pack and Player B wonder picks from that pack; to ‘return the favour’ Player B pulls from a pack to give Player A a chance at wonder picking from that pack. Player A then feels obligated to ‘return the favour’ to Player B, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of reciprocity that encourages continuous engagement with both loot box mechanics.

‘Levelling-up’ – Social Spaces of Competitive Play

Players will earn EXP (experience points) as they play and engage with the game’s various systems such as solo mode, pulling from packs, wonder picking, or playing against other players online. EXP allows players to ‘level up’ and earn a variety of rewards including the in-game currency Poké Gold; as a value-proposition, Poké Gold earned through levelling-up represents a return on investment that gives a player more opportunities to pull from the loot box. Levelling up is however also a status symbol, and the act of levelling, even without additional financial incentive, is motivation enough for some players for social, goal, or challenge reasons (Van Looy, 2010). Attaching a financial incentive to levelling-up adds further enticement for players who are not interested in the challenge or goal orientations of play but are interested in the social orientations of collection and wish to earn more chances – it is prudent therefore for players to level up, utilizing as many ways as possible to do so.The Value of a Card

It is in this way that ‘victory’ is given social and monetary value, and this further translates into an individual card’s value – the ‘real’ value of a card is proportional to both the strength of that card, and the ‘rarity’ of the card. The value of a card does not remain static however; as time goes on new cards will be added to the game to prevent the game from stagnating, and if a player’s current card collection is sufficient to win battles throughout the game’s lifespan, then they will have no incentive to purchase new cards. New sets introduce cards, and these cards may be more powerful than older cards or introduce new strategies to decks around those older cards, causing their value to fluctuate – this is known as “power creep,” which ensures a “perpetual stream of revenue from a single game” (Ham, 2010; Altice, 2016; Švelch 2019). For players who are focused on the competitive motivations of the game, particularly those who engage in tournament play, this means that when they are opening loot boxes in the hopes of obtaining specific cards, they are making speculative purchasing decisions in the hopes that a card becomes more useful or retains its usefulness in the future. This is particularly important for players who engage in tournament play as several community tournaments list cash prizes for winning their events ranging from $50 USD to a staggering $1000 USD (Pokémon Meta, n.d). Even for players who are more focused upon the collection motivation, it is important that they are still able to acquire a good deck that will allows them to compete, at least casually, in online battles. Even if a player has no particular leanings towards competitive play, the degree of prize support available even in community drive tournaments still serves as a very strong motivation to play.

Conclusion: The Need for Public Health Regulation in the Gaming Industry

In this essay I broke down the various deceptive design elements that feature in Pokémon TCG Pockets – its two loot box mechanics, virtual card packs and Wonder Picks – to evidence the urgency with which regulators need to tackle the issue of loot boxes. The popularity of Pokémon TCG Pocket grants it and other games like it a form of pseudo-vindication which encourages other developers to incorporate and expand upon the deceptive design elements I have highlighted in this article. More responsive public health-based regulation is a necessity in order to prevent consumers from becoming vulnerable to emergent harms in games such as Pokémon TCG Pocket, which are particularly appealing to younger audiences. Funding and Conflicts of Interest

GambleAware is funded by money from gambling companies fulfilling a licensing condition from the UK’s Gambling Commission to direct an annual financial contribution to approved organisations working on gambling research, harm prevention, and treatment [1]. It also receives money from regulatory settlements. GambleAware state that “the gambling industry has absolutely no input, influence or authority over any of our activity and those with lived experience of gambling harm inform and guide our work.” [2]. It has an independent board of trustees. At the insistence of my supervisor, the contract for the studentship includes provisions on the research independence of me and the supervising team.

I have never sought, or received, gambling industry funding or payment to conduct research, to testify, or to provide evidence of any kind. I have never sought, or received, payment or funding from private companies or consultancies that profit from problem gambling diagnosis or treatment, or from offering ‘responsible gambling’ services (including ‘safer gambling’ software). I have never sought, or received, payment or funding to advise government agencies seeking to expand gambling.

[1] See Licence Conditions and Codes of Practice Social Responsibility code 3.1.1, here, and https://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/licensees-and-businesses/guide/list-of-organisations-for-operator-contributions#ref-%E2%80%A0

[2] See https://www.begambleaware.org/sites/default/files/2022-10/202216_GA_Briefing%20note_August%202022.pdfdistributing

References

Altice, N. (2014). The playing card platform. Analog game studies, 1(4). https://analoggamestudies.org/2014/11/the-playing-card-platform/

Armitage, R. (2021). Gambling among adolescents: an emerging public health problem. The Lancet Public Health, 6(3), e143. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00026-8

Baqery, M. (2025, January 2). 10 Quality of Life Features Pokémon Pocket Needs. Gamerant. https://gamerant.com/ptcgp-pokemon-pocket-qol-quality-of-life-feature-wishlist/

Brightman, M. (2017, November 20). Loot boxes are not bad game design, say devs. GamesIndustry.biz. https://www.gamesindustry.biz/loot-boxes-are-not-bad-game-design-say-devs

Buergi, J. (2024). Idle Games: A Cozy Genre Turned Exploitative. Replay. The Polish Journal of Game Studies, 12(1), 73–86. https://doi.org/10.18778/2391-8551.12.02

Close, J. & Lloyd, J. (2021). Lifting the Lid on Loot-Boxes: Chance-Based Purchases in Video Games and the Convergence of Gaming and Gambling. GambleAware. https://www.gambleaware.org/media/inochmdq/gaming_and_gambling_report_final.pdf

Craddock, K. D. (2004). The Cardstock Chase, Trading Cards: A Legal Lottery? Gaming Law Review, 8(5), 310-317. https://doi.org/10.1089/glr.2004.8.310

Dark Pattern Games. (n.d.a) Wait To Play. https://www.darkpattern.games/pattern/30/wait-to-play.html

Díaz, R. L. S., Ruiz, G. R., Bouzouita, M., & Coninx, K. (2022). Building blocks for creating enjoyable games—A systematic literature review. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 159, 102758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2021.102758

Dinsdale, R. (2025a, February 5). Pokémon TCG Pocket estimated to have made half a billion dollars in less than three months. IGN. https://www.ign.com/articles/pokmon-tcg-pocket-estimated-to-have-made-half-a-billion-dollars-in-less-than-3-months

Dinsdale, R. (2025b, January 21). Pokémon TCG Pocket Player Crosses 50,000 Cards After Spending More Than $100 a Day for 3 Months. IGN. https://www.ign.com/articles/pokmon-tcg-pocket-player-crosses-50000-cards-after-spending-more-than-100-a-day-for-3-months

Dixon, M. & Larche, C. (2021). Loot boxes as a form of gambling and their potential for contributing to gaming related harm. Critical Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.29173/cgs102

Frommel, J. & Mandryk, R.L. (2022). Daily Quests or Daily Pests? The Benefits and Pitfalls of Engagement Rewards in Games. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 6(CHI PLAY), 226. https://doi.org/10.1145/3549489

Game8. (2025, March 27). Pokémon TCG Pocket (PTCGP) Card Rarity Guide. https://game8.co/games/Pokemon-TCG-Pocket/archives/474500

Game8. (2025, January 26). Pokémon TCG Pocket (PTCGP) How to Use the Wonder Pick Feature. https://game8.co/games/Pokemon-TCG-Pocket/archives/474489

Children’s Commissioner for England. (2019). Gaming the system. https://assets.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/wpuploads/2019/10/CCO-Gaming-the-System-2019.pdf

Gamerefinery. (2022, February 17). The Complete Guide to Mobile Game Gachas in 2022. https://www.gamerefinery.com/the-complete-guide-to-mobile-game-gachas-in-2022/

Ham, E. (2010). Rarity and power: balance in collectible object games. The International Journal of Computer Game Research, 10(1). https://gamestudies.org/1001/articles/ham

Hamari, J., & Tuunanen, J. (2014). Player Types: A Meta-synthesis. Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.26503/todigra.v1i2.13

House of Lords Select Committee on the Social and Economic Impact of the Gambling Industry. (2020). Gambling Harm—Time for Action (HL 2019-2021 (76)). https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld5801/ldselect/ldgamb/79/7902.htm

Kolandai-Matchett, K. & Abbot, M.W. (2022). Gaming-Gambling Convergence: Trends, Emerging Risks, and Legislative Responses. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20, 2024-2056. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00498-y

Lakić, N., Bernik, A., & Čep, A. (2023). Addiction and Spending in Gacha Games. Information, 14(7), 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/info14070399

Petrovskaya, E. & Zendle, D. (2022) Predatory Monetisation? A Categorisation of Unfair, Misleading and Aggressive Monetisation Techniques in Digital Games from the Player Perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 181(4), 1965-1081. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04970-6

Pokémon Meta. (n.d.) Tier List. Pokémon Meta. https://www.pokemonmeta.com/tier-list. Accessed 14 February 2025.

Pokémon Zone. (2025, April 23). How to play Pokémon TCG Pocket? https://www.pokemon-zone.com/articles/how-to-play-pokemon-tcg-pocket/

Ravoniarison, A. & Benito, C. (2019) Mobile games: players’ experiences with in-app purchases. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 13(1), 62-78. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-06-2016-0060

Salmon, C. (2021). Leveling Up: Reminiscing on the Evolution of Gambling within the Video Game Industry. Critical Gambling Studies, 2(2), 166–168. https://doi.org/10.29173/cgs124

Serebii.net [@SerebiiNet]. (2025, Jan 23). Serebii Update: First look at new Binder cover and Display Boards for Pokémon TCG Pocket's Space-Time Smackdown Set https://serebii.net [Tweet]. Twitter. https://x.com/SerebiiNet/status/1882415043935195425

Spicer, S. G., Nicklin, L. L., Uther, M., Lloyd, J., Lloyd, H., & Close, J. (2022). Loot boxes, problem gambling and problem video gaming: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. New Media & Society, 24(4), 1001-1022. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211027175

Švelch, J. (2019). Mediatization of a card game: Magic: The Gathering, esports, and streaming. Media, Culture & Society, 42(6), 838-856. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443719876536

Pokémon TCG Pocket – Card Game [Mobile game]. (2025). The Pokémon Company.

Tondello, G.F., Arrambide, K., Ribeiro, G., Cen, A.J-I., Nacke, L.E. (2019). “I Don’t Fit into a Single Type”: A Trait Model and Scale of Game Playing Preferences. In: Lamas, D., Loizides, F., Nacke, L., Petrie, H., Winckler, M., Zaphiris, P. (eds) Human-Computer Interaction – INTERACT 2019. INTERACT 2019. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 11747. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29384-0_23

Van Looy, J., Courtois, C., & De Vocht, M. (2010). Player identification in online games: Validation of a scale for measuring identification in MMORPGs. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Fun and Games,126-134. https://doi.org/10.1145/1823818.1823832

Villalba-García, C., Griffiths, M. D., Demetrovics, Z., & Czakó, A. (2025). The relationship between loot box buying, gambling, internet gaming, and mental health: Investigating the moderating effect of impulsivity, depression, anxiety, and stress. Computers in Human Behavior, 166, 108579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2025.108579

Wardle, H., & Zendle, D. (2021). Loot boxes, gambling, and problem gambling among young people: Results from a cross-sectional online survey. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 24(4), 267-274. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.0299

Xiao, L.Y. (2021). Regulating Loot Boxes as Gambling? Towards a Combined Legal and Self-Regulatory Consumer Protection Approach. Interactive Entertainment Law Review, 4(1), 27–47. https://doi.org/10.4337/ielr.2021.01.02

Xiao, L.Y., Henderson, L.L., Nielsen R.K.L., & Newall, P. (2022) Regulating Gambling-Like Video Game Loot Boxes: a Public Health Framework Comparing Industry Self-Regulation, Existing National Legal Approaches, and Other Potential Approaches. Current Addiction Report, 9, 163-178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-022-00424-9

Xiao, L., Fraser, T., Nielsen, R. K. L., & Newall, P. W. S. (2024). Loot boxes, gambling-related risk factors, and mental health in Mainland China: A large-scale survey. Addictive Behaviors, 148, 107860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107860

Xiao, L., Petrovskaya, E., Khoo, N., Denoo, M., & Roberts, A. (2025). Widespread Illegal Advertising of Loot Boxes and Social Casino Games in Belgium: Empowered by the EU Digital Services Act to Assess Compliance Using Meta’s Ad Repository. OSF Preprints. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/jc6ks_v1

Yee, N. (2006). The demographics, motivations, and derived experiences of users of massively multi-user online graphical environments. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 15(3), 309-329. https://doi.org/10.1162/pres.15.3.309

Ziegler, J. (2024, October 18). Pokémon Pocket: Pack Hour Glasses, Explained. thegamer. https://www.thegamer.com/pokemon-pocket-pack-hour-glasses-explained/

Comments

Post a Comment