The Walking Dead: Conflicts of Interest in Gambling and Video Gaming Reviewing

By Fiona Nicoll and Mark R Johnson

One of the most successful media franchises of recent years is The Walking Dead, a set of stories focused on survival in a zombie apocalypse. TWD originated as a graphic novel before expanding into a television series (just finishing its ninth season), a number of video games, and a series of “electronic gaming machines” (EGMs) designed by major gambling company Aristocrat. At this link – https://www.aristocrat.com/games/the-walking-dead-ii/ – the trailer for the slot machine makes clear both its connections to the franchise as a whole, and how traditional elements of slot machines have been “rebranded” in the Walking Dead context. These multiple media adaptations make The Walking Dead an exemplary set of texts for examining and unpacking some of the intriguing differences between gambling and video gaming versions of a media item. Specifically, they allow us to compare how processes of product reviewing are understood, framed, and performed. With new gambling and gaming products arising on a regular basis, and being mediated and understood in part through their online representation, it is useful to explore how communities address issues involved in reviewing. We will see that, while game reviewers are often explicit about their relationships with developers and how they acquired the games in question, some go further and discuss potential conflicts of interest. In contrast, the relationship between gambling product developers and reviewers is strikingly opaque: why is this, and what might be done about it?

How to Cite: Nicoll F., & Johnson M. R. (2019). The Walking Dead: Conflicts of Interest in Gambling and Video Gaming Reviewing. Critical Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.29173/cgs11

To begin with we ask: what do reviews do for media products? Reviews are an easily overlooked element of contemporary media ecosystems. Although we might like to believe we are rarely influenced by them, choosing instead to go our own way, reviews fundamentally shape the cultural reception and profitability of media goods. In the context of video games, game reviewing has seen a move from text, to video, to live-video (produced by primarily "amateur" content creators). In gambling, meanwhile, we see the emergence of slot machine reviews, seemingly from average punters giving apparently honest appraisals of the products at hand. Gambling and video games both entail play, generally involve money in some manner, undergo testing, and they are reviewed once released by external actors, who then inform consumers about potential purchase or play decisions. Despite these overlaps, we have discovered profoundly different expectations for reviewing, through which we can explore questions of transparency, trust, and conflicts of interest. We will argue that, whereas gamers have (now) organised as a quasi-public sphere in which standards of transparency and disclosure are expected, this has not occurred with EGM players; their evaluation of gambling products are rarely visible beyond academic literatures of addiction and related journalism and political advocacy.

Games Testing

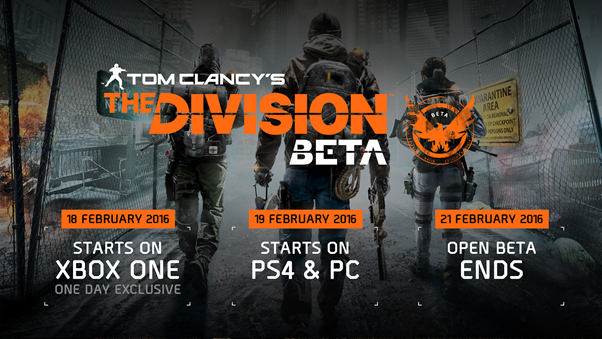

Many digital game studios until the last decade performed exclusively what was known as “closed testing”. This meant that games were tested internally at the development studio or development team who were leading on the project, often once the project reached the point of a “beta” – an early and incomplete, but functionally playable, copy of a new digital game. Traditionally feedback was primarily qualitative in nature, although more recently companies have implemented methods for acquiring quantitative feedback on what is happening under-the-hood, as well as what the player perceives. Today, however, many games are developed through open testing, where a beta version is released for players to experience, send feedback on, and generate data on for the company. In this way many players now contribute to the shaping of digital games (this process continues after release through an iterative feedback-update loop). Many have rightly criticised the “release” of “unfinished games” – most recently notoriously 2018’s Anthem, which according to a developer, wasn’t playable right up to release because “there was nothing there. It was just this crazy final rush” (quoted in Schreier, 2019) – via systems of this sort. However, these developments have also led to a situation where the process of game making has become more transparent than ever before, at least at the later stages of development. Testing has also become an ongoing, iterative process: for examine, in Star Wars: Battlefront II (2017), a “loot box” system was considered so exploitative, and consequently became so unpopular, that it was removed after public outcry; in Destiny 2 (2017), players found deception in the game’s systems, which were also removed in later versions. Player feedback thus sometimes enables players to resist elements of play they find undesirable, and with a sufficiently large resistance, change will sometimes take place.

Gambling Testing

Whereas some aspects of video game testing have become more transparent, what can be said of gambling testing? Slot machines are the primary area where new gambling forms emerge, and tests are routinely needed to ensure these devices function as intended. In most cases electronic gaming machines are tested behind closed doors, before being revealed to the public, after which their profitability (or lack thereof) usually determines their longevity and location in particular gambling venues. Players have little direct input into this process and are rarely provided with avenues to leave comments or criticisms of their experience: it is a matter of consumption, rather than co-production, of the final play product. Whereas video game testing has traditionally been a matter of making the experience as close as possible to what players will find enjoyable and rewarding, avoiding exploitation (although certain major games companies no long prioritise this), EGM production is focused on maximising player retention or ‘time on device’ (See Schüll, 2012). Although this line is blurring in video games through design mechanics such as loot boxes, clear differences remain between these systems for delivering entertainment and play. One of the most important is related to the consumer base for video games and electronic gaming machines and, hence the audience of reviews. While digital games are directly marketed to a large consumer base, which often includes children, EGMs are marketed to venue owners at large conventions who cater to a relatively small population of committed adult patrons. Notwithstanding these differences, however, we will see that apparently shared genres of reviewing have emerged over the past decade.

Game Reviewing

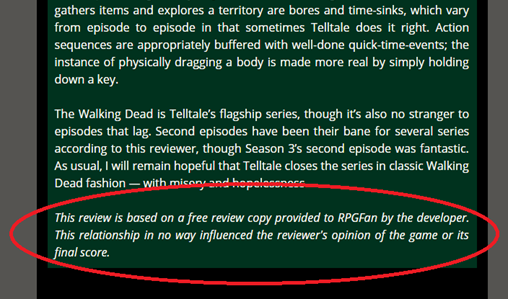

We have discussed how games and gambling testing function – but what about the reviewing of the final products? Traditionally, games journalism has involved writing an article which includes some screenshots of the game in question, or producing a video, perhaps ten minutes long, which shows relevant (but spoiler-free) parts of the game in question. Reviewers would gain access to these games through “review copies” distributed by developers, but were generally not beholden to the developers to give positive reviews. These individuals were professional reviewers, and always acknowledged as such, even if some games companies were reluctant to submit their products to critical scrutiny. In recent years, games reviewing has increasingly shifted to video-sharing site YouTube, where reviewers can deploy high production values such as editing, green-screen and animated transitions; but with this shift to “amateur” reviews, they are expected to explicitly acknowledge where games came from. Unclear provenance of the games being reviewed, or an unstated relationship between reviewer and developer, is considered strongly unacceptable.

The most recent development is live streaming of video games, exemplified by website Twitch.tv (Johnson & Woodcock, 2017), which hosts video content made by two million broadcasters – each year. Twitch changes how we learn about new games through informal “reviews” which take place during the place of new games: a viewer can watch for as long as they want, get live comments, and talk to the “reviewer”. This has made live streaming a major site for deciding what to purchase, and represents a unique, back-and-forth, conversational, form of reviewing. As on YouTube, streamers must make it clear if their stream was “sponsored”, and sometimes even elaborate on their relationships with games companies. In fact, the use of COI statements in gaming has now become something of a self-reinforcing norm, not just something that the most meticulous or assiduous reviewers do. Players have come to actively expect it from their reviews, and in many cases will become suspicious or doubtful if this expectation is not met. The community has taken it upon itself to “police” this element of the gaming ecosystem, to ensure their reviews are impartial - or, at least, as impartial as possible. However, the ubiquity of amateur content production makes it equally vital that conflicts of interest are addressed in the reviewing of gambling products.

Gambling Reviewing

The rise of consumer recommendations and ‘influencers’ through YouTube and other social media platforms has generated new ways to promote digital gambling products. Despite the complex legal, political, economic and social entanglements of gambling there is almost no oversight present for the reviewing of gambling products or experiences by users; consequently reviews and marketing blend with surprising and concerning ease. For example, we would note the existence of websites with casino deals that give recommendations for different online slot providers, and information about how to play EGMs. These sites are similar to “portals” on the early internet – they bring together all sites/platforms of a certain sort in one place, sort them, rate them, and link to them, yet also serve as direct advertising from casinos. Secondly, and perhaps most concerningly, is a genre of “slot reviews” on YouTube, where players record jackpots and “features” arising from EGM sessions (Nicoll, 2011, 249). Features are a sequence of free games triggered by a sequence of symbols on virtual reels and often involve animations and sound effects that are similar to video games. For example, “Slotlady” is a young, well-presented, woman who records her successful slot play, attracting a healthy cohort of followers who participate vicariously in the features she wins. She introduces a video of herself playing the Walking Dead slot machine by sharing her initial stake with viewers as well as the fact that she is playing the maximum bet of 375 credits. After recording her session in what appears to be real time, she completes her video with a statement of the profit ‘earned’ and an invitation to subscribe to her YouTube channel as well as her channel on Patreon. In another video, Slotlady shares the name of the casino where she won an ‘incredible bonus’. As with Twitch reviews, the recording of gambling by users/consumers appeals to viewers as more authentic than traditional advertisements. But while she is recognisable as a professional influencer, at no point in her videos is the relationship between Slotlady and the EGM companies and casinos where she wins clarified to us.

How are we to understand the role of influencers within the word of digital gambling? Gambling has always had its celebrities: larger-than-life individuals known for famous games, great wins, great defeats, or the opening of well-known casinos. These figure drew the general public into gambling as a potentially exciting and thrilling passtime through the dramatic nature of their exploits (real or elaborated). Little if any profit was made from indirect dissemination activities they performed. Social media influencers serve a different role: they are not the world-famous gambling celebrities - who certainly still exist - but rather embodiments of every person who hope to find success in their gambling activities. Influencers don’t play the high stakes games in closed rooms - they play the same stakes as you do, on publicly visible machines on the casino floor. And it is precisely this apparent commonality, which makes them so effective at their jobs and conflicts of interest so important.

A notable aspects of many of these videos is that they are often produced in casinos, in spite of widespread prohibitions on photography and recording in these venues. This illustrates a strong tension between the regulatory frameworks that govern gambling and restrict its promotion – on one hand – and a social media infrastructure which allows smartphone users to record their winning experiences in casinos – on the other. Rules against recording in casinos are historically grounded on several considerations. Firstly, venues operated by private companies are concerned with protecting how their brands are publicly represented. Secondly, because gambling is not available to minors, videos depicting people winning in casinos could be construed as promoting gambling to individuals who are under-age. Thirdly, like prostitution and in contrast to most gaming, gambling is culturally framed and politically regulated as a “legal vice” in jurisdictions where it is allowed; as a consequence, stigma can attach to consumers who are photographed in gambling spaces. This makes the reviewing of gambling products via social media platforms a particularly complex and ethically fraught issue.

Conclusions

We have investigated differences between testing, reviewing, and procedures to address conflicts of interest in gaming and gambling products. With digital games, player-influencers have taken the importance of acknowledging conflicts of interest to heart, strongly emphasising any potential relationships between their own media production and the games they are provided with. In gambling, however, we see a blurring of interests between the influencer, the slot machine company, and the casinos which house them, in large part created by the newfound ability for websites like YouTube to effectively market to diverse crowds. This means that consumers who are nominally breaking rules – although it seems likely many are allowed to do by casinos – are able to implicitly promote the casinos they play with in, while also editing their videos to convey a positive sense of play to their viewers. It would be easy to read this discrepancy as evidence that slot players are dumb or gullible, to conclude that, whereas gamers have a deep cultural distrust of sponsored content, EGM players do not. This resonates with academic scholarship on problem gambling which emphasises the “flawed thinking” of individuals who play EGMs. However, it is clear that savvy slot players have been able to monetise videos of their play and offer advice and comments as influencers via social media platforms. It is perhaps less accurate to see these video producers as victims connected to exploitative machines than as functioning parts of social media networks where individuals earn money by representing their consumption in particular ways.

Our comparison of video game and gambling product testing and reviewing raises some important questions about the political and cultural economies of social media platforms and the contents they allow and enable. Where are the communities of players concerned over the ethics of slot reviewing? And where is the interest by academic researchers and policy makers on the principle means by which digital gambling is promoted in the second decade of the twenty first century? As the borderlands between digital games and gambling continue to expand through the incorporation of loot-boxes and other slot-like game mechanics into the former, more attention is needed to bear on how conflicts-of-interest issues impact consumers of media and entertainment more broadly. At stake is not just how companies or influencers themselves behave, but the political effects of cultural systems of judgement which continue to distinguish consumers of video games from consumers of digital gambling products. To engage with the imagery of our case study of the Walking Dead, it is time to dispose of ineffective yet undead ways of regulating gambling, such as information sheets and signage in venues and to adopt more transparent processes of testing and reviewing products such as we have found in the world of gaming.

Comments

Post a Comment