A Response to Gambling Studies’ #MeToo Moment

Fiona Nicoll, Murat Akcayir

How to cite: Nicoll F., & Akcayir M. (2020). A Response to Gambling Studies’ #MeToo Moment. Critical Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.29173/cgs63

In

recent weeks, the world of gambling research has been shaken by a “#MeToo”

moment. Founded by African-American activist, Tarana Burke, in 2006 as a way to

connect survivors of sexual assault to other women and resources for healing,

MeToo was popularised as a hashtag in 2017 with revelations of heinous abuses

of power by Hollywood film producer Harvey Weinstein and casino magnate, Steve Wynn,

as well as many other high profile men in the worlds of business, politics,

entertainment and academia. (Hess, 2017, Mansfield, 2019) Gambling’

studies’ #MeToo moment involved a senior male academic researcher as the

subject of a complaint against a colleague from another country and

university. He was accused of sexual stalking and - following media

publicity - resigned from his university. The complainant was an early career

researcher with a capacity building role related to gambling research in her

university. She had allegedly experienced

intense and unrelenting sexual attention for nearly two years after terminating

earlier consensual interactions with a man who she had initially valued as a

mentor. After her new partner sent angry texts demanding that the senior

researcher desist, the latter told the complainant that he would not only cease

contact, he would also cut professional ties with her, including involvement in

forthcoming research proposals. It was at this point that she decided to lodge

a complaint. She explained to a media source that gambling research is a

relatively small and close-knit community and that bad relations with her

former mentor were likely to irreversibly damage her career. We do not want to

dwell on the individuals

involved in this case. Instead we cite these details as a starting point

to encourage further research on characteristics of gambling research which

reproduce structures of social

injustice.

We are unconvinced by explanations of this case that point to malicious intentions or individual pathology as the primary cause of physical, sexual or psychological harassment and violence. The naming and shaming and punitive treatment of individuals whose unethical behaviours are exposed can bring an immediate sense of relief or vengeance. But it can also paradoxically entrench injustice, by appearing to have expunged or resolved more intractable features of institutional cultures. We suggest that the best way to understand and to eliminate this violence is by combining data-driven and theoretical approaches to the problem. A valuable theoretical framework to understand structural and institutional oppression has been developed by Sara Ahmed - a scholar who brings empirical studies of equity and diversity work together with philosophical insights from feminism, queer theory, critical race theory and phenomenology. We use her work, together with evidence from our current meta-analysis of gambling research, to understand some of the barriers to gender justice in our field and to suggest some ways forward.

According to Ahmed, the mere existence within institutions of formal complaint processes to address discrimination, violence and harassment, is no guarantee that these will be used for the purpose for which they are designed. Indeed, they may be ‘non-performative’ documents, the very existence of which enables discrimination to persist as usual. She explains how, in the everyday life of academic institutions, formal processes of complaint are often surrounded by warnings about possible implications of their use. As she explains:

A would-be complainer is one who has taken some steps

in the direction of a formal complaint, perhaps by making an informal

disclosure to a line manager, supervisor, or peer. Many complaints are stopped

at this point through the use of warnings… A warning is an ominous sign, a sign

of the danger-to-come. Warnings surround complaints as if to say to proceed is

to endanger your own person. Warnings are typically stronger than advice about how

to proceed; they are often issued in an emergency. When an emergency is

implied, an instruction is given about how to treat a situation … The

implication is that to proceed with a formal complaint is not to think about

your career; being advised not to complain is offered as career advice. Your

career is evoked as a companion who needs to be looked after. Maybe your career

is a plant that needs watering so that it does not wither away; if your career

would wither as a consequence of complaining, then a complaint is figured in

advance as carelessness, as negligence, as not looking after yourself. (158-9)

This sense of ominous outcomes awaiting women who dare to complain was a common theme in many of the testimonies made by women who had been sexually assaulted by Harvey Weinstein. If they mentioned the abuse to others in the Hollywood industrial network, he would counter with a claim that the actors were ‘difficult’ to work with. In this way a complainant is reduced to a complaint that can be made and circulated by the perpetrator.

In the case under consideration here, the early career researcher had been extremely reluctant to make a complaint, worried about the effect this would have on her career. It was only when her harasser directly threatened her with some adverse career outcomes that could follow cessation of his unwelcome sexual attentions that she decided to go ahead with the complaint. His warning had placed her in an impossible situation. She required international networks to fulfil the requirements of her academic position. This required, in turn, evidence of collaboration on peer-reviewed publications as a proxy for academic excellence, as well as evidence of collaboration in public-facing activities such as conferences, reports, reviews and policy recommendations that make up the ‘grey literature’ of gambling studies. There is considerable overlap between these types of collaboration in practice; gambling is regulated by states which require and solicit reports and reviews to inform and justify their policy decisions. Thus, a perceived failure to network successfully within the relatively small community of researchers who publish in the main scholarly journals and are commissioned to assist with major government studies reports would indeed have significant career impacts.

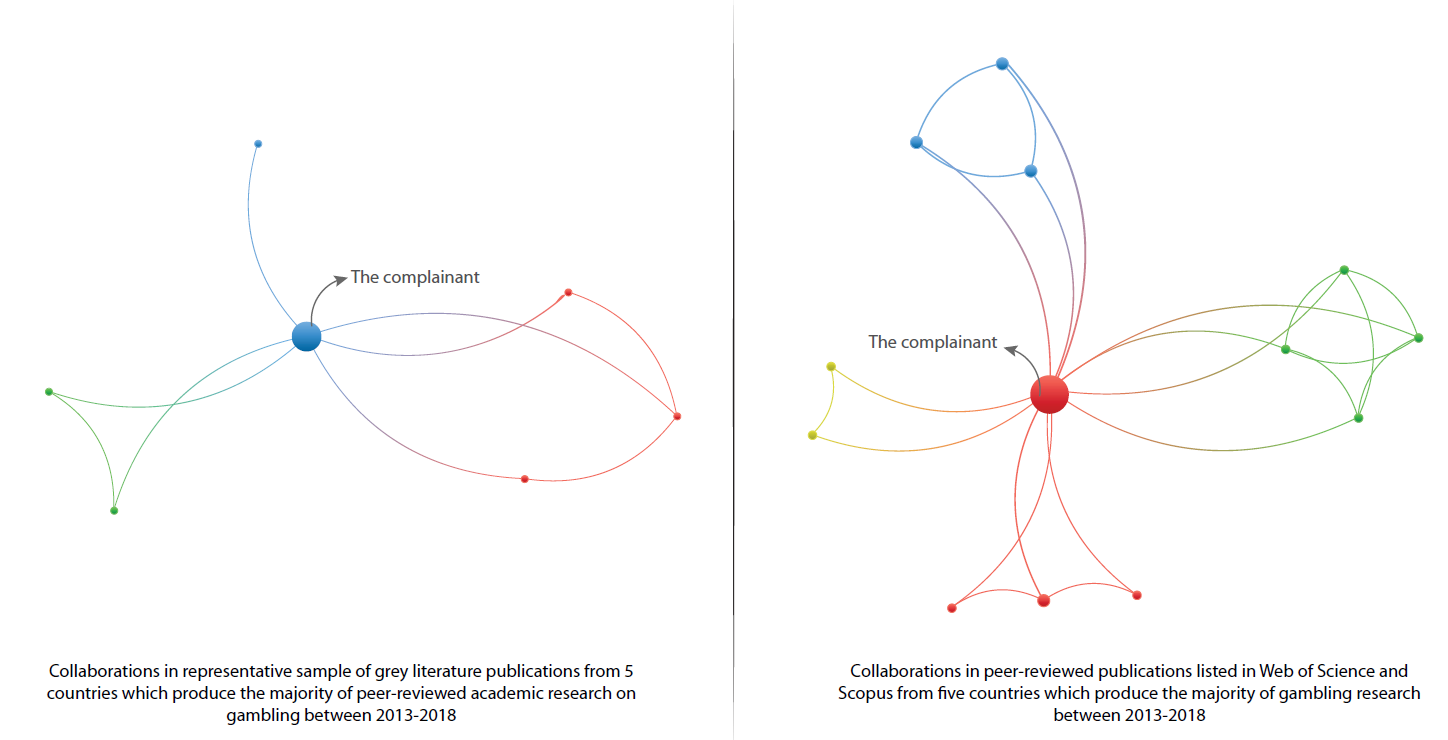

The mobilisation of big data is increasingly being used by scholars to move beyond statistical studies that focus on raw numerical representation to understand deeper and consistent patterns of discrimination in specific sectors. Recent studies, such as Verhoven et al (2020), use social network analysis (SNA) to empirically understand the dynamics through which women’s exclusion occurs, and to evaluate scenarios that might ameliorate persistent problems in specific industries. Building on such approaches, we can develop an understanding of sexual harassment in gambling research that goes beyond the acknowledgment of individual ‘bad apples’ and the assumption that an increase in women’s representation will necessarily change the field in a positive way. We analysed metadata of peer-reviewed gambling research from five countries (in alphabetical order: Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK, and the USA) which generate the most articles listed in Scopus and Web of Science databases, as well as representative grey literature publications. This exercise produced useful evidence about the potential impact on an early career scholar of severing a relationship with a high profile researcher in the field.

We considered the gender ratio among the ten

most-cited active researchers in the field, as well as the comparative scope

and scale of networks in peer-reviewed publications and in the grey literature.

And we found that the ratio of representation of male to female

researchers for the most cited articles - where men are overrepresented at

8:2 - is less important than a series of interrelated factors.

The metadata highlights two structural

factors that support the claimant’s concerns and show how younger, female researchers

are vulnerable to abuses of power. The first structural factor is the role

played by citations in peer-reviewed journals - which are often ranked, in

turn, by their impact factors - as a proxy for academic impact and excellence

by academic search and tenure committees. This is notwithstanding volumes

of research documenting the limitations of article and journal impact factors

as well as double blind peer review. (see for example, D’Andrea, R.,

& O’Dwyer, J. P. 2017; Lee et al 2013, Mallard et al 2009, Amin and Mabe,

2003, Erne, 2007). A dramatic example of the limitations of peer-review is the recent

retraction of an article on COVID-19 treatments which was based on dubious data

by the prestigious Lancet journal of medical research. In spite of

the evidence against simple bibliometric evaluations of academic performance,

pressures to automate appraisal systems in universities to cut costs have never

been greater. Without citations in high impact journals, the career of an early

career academic today is likely to be precarious, at best.

The second structural factor is the extremely high proportion of joint authorship in the field of gambling research. This is consistent with a trend over time which has seen the field dominated by psychiatry and neuroscience and psychology and health while humanities, law and social science - where sole authorship is far more common - have become increasingly marginalized.

When we look at the field of gambling

studies, it is clear that certain disciplines predominate. Our previous bibliometric analysis of

disciplinarity by journal self-identification demonstrates that the majority of

gambling scholarship is published in psychology and health and psychiatry and neuroscience. In the case under consideration, the senior researcher’s field is

psychology/health, while the complainant’s field is in anthropology/psychology. Arguably the complainant is further disadvantaged by her academic

background in anthropology, a social science where sole authorship is relatively

common. This is in contrast to the senior researcher, a psychologist in

public health, a field where co-authorship is the most common process for

academic output. The rise of the psy-health

disciplines in gambling studies is reflected in the decline of sole authorship

of peer reviewed articles on gambling - from c.43 percent between 1996 and 2014

down to c10 % between 2014 and 2018.

We excluded the large body of interdisciplinary research from our analysis. Our previous research showed that only a minority of journals that self-identify as ‘interdisciplinary’ actually published research from disciplines beyond those which already dominate the field. We found no significant differences between that the research questions, methodologies and arguments of articles in this interdisciplinary category and those in journals that self-identity as publishers for research in neuroscience, psychiatry, health and psychology.

|

problem |

2113 |

pathological |

615 |

severity |

425 |

|

study |

1312 |

social |

611 |

reported |

421 |

|

risk |

911 |

associated |

572 |

casino |

414 |

|

results |

879 |

Self |

569 |

online |

403 |

|

treatment |

823 |

Sample |

534 |

studies |

400 |

|

problems |

771 |

Data |

503 |

higher |

399 |

|

research |

757 |

behavior |

491 |

health |

396 |

|

related |

714 |

Non |

467 |

significant |

387 |

|

participants |

647 |

findings |

456 |

high |

383 |

|

use |

618 |

Using |

449 |

factors |

369 |

Top thirty words from abstracts of articles published between 1996-2018 in peer-reviewed journals that identify as 'interdisciplinary', listed in Scopus and Web of Science in the 5 countries of the study.

It is not an exaggeration, then, to claim that success

in gambling studies requires very strong networks of collaborators and that

most potential collaborators for early career researchers are likely to be

found in the psy-science and health disciplines. We can now use the

metadata evidence to evaluate the complainant’s claim that souring relations

with the senior academic who had been harassing her could seriously damage, if

not end, her career.

We see that the senior researcher is the most cited author in his nation with 102 publications; he is lead author on 41 peer reviewed articles and co-author on 61 peer reviewed articles. He is also author or co-author of 33 grey literature publications. He is in the top 25% of most cited authors overall and has collaborated with three researchers in the top 10 of those who are most cited on 5 grey literature projects. He also has eight peer-reviewed publications with an author in the top 10. His international networks span collaborations with colleagues in eight countries. And - notably - 35 percent of his collaborations in peer-reviewed publications are with gambling researchers in the complainant’s home country. These are individuals whose evaluations might well be sought in order to inform decisions about the complainant’s future tenure or promotion case. The highest impact factor of journals the senior researcher has published in since 2013 is 6.85 and the average impact factor is 2.767. His current h-index score is 54.

In

comparison, the complainant, who completed her PhD in 2013, is ranked 4850

among (8008 identified) gambling researchers in the 5 countries, with 5

articles as lead author and 1 article as co-author. She has not

collaborated with any researchers among the 10 most-cited. The average

impact factor of the journals that the complainant’s articles were published is

1.985 and her h-index score is 5. We should also note that the complainant and

the senior researcher have separately collaborated with 2 researchers in common. When

all of these factors are considered together, we can make a reasonable

prediction of how the role a breakdown in her relationship with the senior

researcher would play in jeopardising her career.

It is important to clarify here that we are not

arguing, either that the senior researcher would

in fact disparage the complainant to potential collaborators, nor are we

arguing that potential collaborators would necessarily believe the senior researcher’s claim. Returning to Ahmed’s

argument cited above, all that is necessary for the complainant’s career to be

affected is the existence of a warning and the threat of retribution that will

hang over her as she tries to avoid the senior researcher and the many people

within his academic and policy networks.

Where to now?

What are some

constructive ways that researchers and academic institutions might respond to

gambling studies’ #MeToo moment? We have used Ahmed’s research on the institutional

politics of complaint, together with gambling research metadata, to argue that

it is not simply a matter of counting, mentoring, and otherwise encouraging

women to take and maintain a place in the field. Rather, deeper changes are needed to

transform the structure of the field so that early career researchers – and

women in particular – are less targetable for sexual abuse.

The most obvious thing we can do is to highlight that the making and just resolution of complaints is the strongest evidence that sexual abuse will not be tolerated in our field. The second thing we can do is take practical steps to encourage more sole authorship and to cultivate a more genuinely interdisciplinary research environment in gambling studies. This will relieve some of the current pressure on early and mid-career researchers to collaborate on projects and will expand the scope of potential colleagues available when they do choose to collaborate. We must also support and fund more independent fora for early career researchers so that lateral knowledge relationships can interrupt hierarchical systems which currently make powerful (and often male) mentors necessary to survive and progress in the field. The fact that the first special issue of Critical Gambling Studies will not only be dedicated to showcasing the work of early career researchers but will also be edited by them, is a move in the right direction.

In conclusion: we need to be more explicit in defining and sustaining the ethical standards needed to sustain productive collaborations between researchers in our field. Persisting with unwanted sexual communication and threatening careers when complaints are made should not be tolerated by colleagues or university administrators, regardless of the research and service contribution record of perpetrators. To guard their integrity and institutional reputations, University authorities will have to take a gamble in the race for more rigorous and interdisciplinary knowledge of gambling. Do they continue to put their money on the favourite scholar, the man who has garnered prestigious awards and profits in the past, turning a blind eye to his harassment and threatening behaviours? Or do they put their money on a stable of promising new scholars and demonstrate zero tolerance for behaviour that creates an invisible handicap for younger women in particular?

References

Ahmed, S. (2019). What's

the Use?: On the Uses of Use. Durham: Duke University Press.

D’Andrea, R., & O’Dwyer, J. P. (2017). Can editors

save peer review from peer reviewers?. PloS one, 12(10), 1-14.

Hess, A. (2017, November 10). How the myth of the artistic genius

excuses the abuse of women. New York Times. Retrieved from

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/10/arts/sexual-harassment-art-hollywood.html?_r=1

Lee, C. J., Sugimoto, C. R., Zhang, G., & Cronin,

B. (2013). Bias in peer review. Journal

of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 64(1),

2-17.

Mallard, G., Lamont, M., & Guetzkow, J. (2009).

Fairness as appropriateness: Negotiating epistemological differences in peer

review. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 34(5), 573-606.

Mansfield, B., Lave, R., McSweeney, K., Bonds, A.,

Cockburn, J., Domosh, M., ... & Ojeda, D. (2019). It's time to recognize

how men's careers benefit from sexually harassing women in academia. Human

Geography, 12(1), 82-87.

Verhoeven D, Musial K, Palmer S, Taylor S, Abidi S,

Zemaityte V, et al. (2020) Controlling for openness in the male-dominated

collaborative networks of the global film industry. PLoS ONE 15(6): e0234460. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.

pone.0234460

Comments

Post a Comment