The “New Buffalo” Confronts a Pandemic: Implications of the COVID-19 Shock for the Indigenous Gaming Industry

The “New Buffalo” Confronts a Pandemic: Implications of the COVID-19 Shock for the Indigenous Gaming Industry

Laurel Wheeler

This non-peer reviewed entry is published as part of the Critical Gambling Studies Blog.

How to cite: Wheeler, L. (2021). The ’New Buffalo’ Confronts a Pandemic: Implications of the COVID-19 Shock for the Indigenous Gaming Industry. Critical Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.29173/cgs93

“It’s

really pretty much crippled our tribal economy…The casinos are the bread and

butter of our funding.”

- Marlon

WhiteEagle, president of the Ho-Chunk Nation (in Wisconsin State Journal, June 2020)

“Life and

death…We’re just going to write off 2020. There’s no sense in trying to work

under the delusion that we’ll be able to claw back to normal life this year.”

- Bryan Newland, tribal chairman of the Bay Mills Indian Community (in New York Times, May 2020)

Abstract: The COVID-19 pandemic is

an economic shock that affects both the supply of and demand for goods and

services. These effects are particularly profound in the hospitality and

leisure sector, which includes the gaming industry. COVID-19 therefore has the

potential to result in lasting damage to localities that depend on gaming

revenues. For Indigenous gaming communities, the stakes are especially high.

The Indigenous casino and gaming industry has been characterized as the coming

of the “new buffalo[1],”

a trope that alludes to the high levels of wealth enjoyed by bison-reliant

communities in the Great Plains. Indeed, Indigenous gaming has been a valuable

engine of economic growth for many communities across North America, but

COVID-19 reveals this economic success to be a double-edged sword. The COVID-19

shock is now threatening to undermine an industry that has come to play a

critical role in the physical and financial health of Indigenous gaming

communities as well as in their capacity to exercise their right to

self-determination.

Click below to listen to an interview

with Joseph P Kalt, Co-director of the Harvard Project on American Indian

Economic Development: “COVID-19 has closed tribal casinos and cut off other

vital revenue sources”

Two Economic Shocks in One Pandemic

More

than one year after the novel coronavirus was first identified in humans, nations

across the globe are experiencing a second wave of COVID-19 infections. In many

places, this second wave threatens to be more injurious than the first, putting

additional stress on already-weakened health care systems against the backdrop

of an economic downturn. In an effort to slow the spread of the virus, local

and national governments across North and South America, Asia, and Europe are

instituting another series of restrictions on travel, activities, and

gatherings. Inevitably, each new set of COVID-19-related restrictions renews

debate about how to manage a health crisis and an economic crisis

simultaneously.

From

an economic standpoint, COVID-19 represents a severe, unanticipated shock with

the particularly pernicious feature of affecting both supply and demand.

Restrictions implemented to benefit public health come at the cost of

production. Lockdowns that prevent workers from doing their jobs and social

distancing measures that force businesses to close are examples of shocks that

affect the supply of goods and services. But the COVID-19 pandemic is not only

a short-run supply shock that comes and goes with the tightening and relaxing

of restrictions. We now know that COVID-19 initially emerged as a supply shock

but later led to an even larger demand shock (Guerrieri et al., 2020). A demand

shock is anything that affects consumers’ ability or willingness to purchase

goods and services at a given price. As unemployment rises and consumers cut

back on spending, demand for goods and services continues to plummet. The dual

nature of this economic shock is rare, perhaps most often associated with

natural disasters.

The Casino and Gaming Industry takes

a Direct Hit

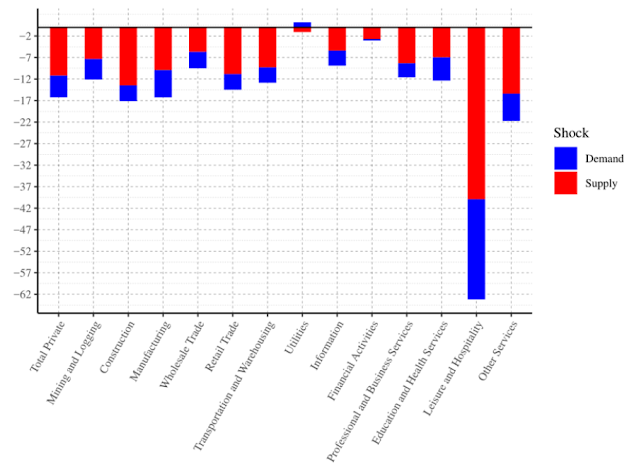

Although

the COVID-19 shock pervades large swaths of the economy, it does not affect all

sectors equally. At the start of the pandemic, economists began to make

predictions about sectoral vulnerability to the COVID-19 shock (see, for

example, the

analysis by Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s). The consensus

view was that the leisure and hospitality sector, characterized by face-to-face

interaction and close physical proximity, would be among the most “at-risk.”

This is compared with the finance, insurance, or health care sectors, which

were generally regarded to be shielded from the worst damage. Those predictions

were borne out in the early months of the pandemic. Estimates using data from

the United States indicate that the initial damage to the leisure and

hospitality sector dwarfed the damage to other sectors, both in terms of supply

and demand effects (see Figure 1). And situated

squarely within the leisure and hospitality sector is the casino and gaming industry.

Figure 1:

Shock Decomposition for April 2020

In

March 2020, S&P Global Market Intelligence identified the casino and gaming

industry as one

of five industries most at risk of default in the United States. At

the time, casinos across the world were closing their doors as governments tried

to buy time to develop a cohesive response to a novel disease. In a 72-hour

period in March, Canada shut down almost all of its 114 casinos (Stevens,

2020). Those closures corresponded to millions of dollars in lost revenue in

several provinces, including Manitoba

and Quebec.

Across the border, casino closures in the United States contributed to second

quarter gross revenue losses measuring in the billions of dollars (American Gaming Association, 2020).

As

you can see from Figure 2, the near-complete shutdown of the casino and gaming

industry was relatively short lived. The majority of gaming properties in North

America had re-opened by the end of the second quarter of 2020. The September

update posted by S&P Global Market Intelligence had removed the

casino and gaming industry from their list of five industries most likely to

default. But that doesn’t mean the gaming industry is out of the woods yet. The

pandemic’s second wave is responsible for another round of closures. And until

the macro economy improves and the inherent risk associated with being in close

proximity to other people is mitigated, demand for traditional gaming options

like casinos is likely to remain below 2019 levels.[2]

We

should care about the economic damage to the casino and gaming industry not

only because we care about the industry, but also because we care about the

communities that depend on it. Localities that rely heavily on gaming will be

disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 shock. If these places lack diversification

in their industrial base, they are left with no insurance against the shock,

leading to widespread furloughs, unemployment, and lost wages within the community.

With this concern in mind, The

Brookings Institute conducted an analysis that ranked metropolitan

areas in the United States by exposure to the economic effects of COVID-19

based on the share of jobs in high-risk industries (see Figure 3). Two of the

top five most exposed metropolitan areas are among the world’s most prominent

casino cities: Atlantic City and Las Vegas.

Figure 3:

Share of Jobs in Industries at High Risk from COVID-19 across the United States

Notes: Map created by the Brookings

Institute using Zandi (2020) definitions of “at-risk” industries. The figure can

be accessed at: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2020/03/17/the-places-a-covid-19-recession-will-likely-hit-hardest/

The Economics of Indigenous Gaming

Counted

among the localities that specialize in the casino and gaming industry are many

Indigenous communities across North America. The 1988 passage of the Indian

Gaming Regulatory Act gave rise to a rapid proliferation of gaming facilities on

federal reservations across the United States (see Figure 4). Today, more than

400 casinos operate on reservations in 29 states, generating gross revenues

that exceed $30 billion annually (National Indian Gaming Commission, 2020).

Many tribal governments have invested heavily in the casino and gaming

industry. By and large, those investments have paid off. Although experiences

have not been uniform, most gaming communities have benefited from sustained

revenues, which they have invested in a range of anti-poverty programs and

tribal services (Akee et al., 2015). For example, Cattelino (2010) details how

the Florida Seminoles allocate their gaming revenues to health care and

education infrastructure, cultural programs, and economic diversification

projects ranging from cattle ranching to venture capitalism. The Indigenous

gaming industry in Canada is much smaller in scale but nonetheless important to

the First Nations that operate 19 for-profit and charitable casinos, together

generating more than $1 billion in gross revenue annually (Belanger, 2014).

Figure 4: The Evolution of Indigenous Gaming in the United States, 1990-2014

Notes: Author’s own production using Census reservation shapefiles and data on casino openings on federally recognized reservations across the United States (Wheeler, 2019).

The Vulnerabilities of

Casino-Reliance

Particularly

in the early days, Indigenous gaming was hailed as an economic development

panacea. It was described as “the new buffalo,” drawing comparison to the

historical importance of the North American bison to many Indigenous

communities throughout the Plains, the Northwest, and the Rocky Mountains. For

10,000 years, these communities relied on bison for food, clothing, blankets,

and trade. The bison was the backbone of their economies and a source of

prosperity. Comparing Indigenous gaming to the North American bison underscores

the perceived importance of the industry to the prosperity of Indigenous

communities. It also raises questions about the vulnerability of gaming

communities to economic shocks. European settlers hunted

the bison to near-extinction in the late 19th century,

devastating the economies of the bison-reliant communities. Economists at the

University of Victoria have shown that the slaughter of the bison was so

destructive to bison-reliant communities that the negative effects persist to

this day in the form of both economic and physical outcomes (Feir et al.,

2019).[3] It

would be inappropriate to stretch the “new buffalo” analogy to generate predictions

about the impact of the COVID-19 shock on casino-reliant communities. [4] Nevertheless, the destruction of the bison

illustrates the inherent economic vulnerabilities associated with lack of

diversification.

The

shuttering of tribal casinos in the United States between March and May 2020

resulted in 300,000 people out of work, $997 million in lost wages, and

approximately $4.4 billion in lost economic activity overall (Meister Economic

Consulting, 2020). Indigenous casinos employ members of the community as well

as non-members, so the economic effects of casino closures extend beyond the

boundaries of the reservation or reserve. Most worrying is the effect of lost

casino revenue on Indigenous gaming communities. Unlike state or local

governments, tribal governments have no tax base. For the Ho-Chunk Nation, the

Oneida Nation, and many other gaming communities, casino revenues comprise the

vast majority of the tribal government’s operating budget. Marlon WhiteEagle,

president of the Ho-Chunk Nation, described the casino closures as “crippl[ing]”

to their tribal economy (Wisconsin State Journal, 2020). In the

embedded interview at the top of this post, Joseph Kalt, Co-director of the

Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development, tells of the

pervasiveness of these debilitating effects. He explains that, due to COVID-19,

Indigenous gaming communities “run a risk of reversing about 30 years of slow,

but steady progress.”

The COVID-19 Shock Wave: Beyond

Economics

The

COVID-19 threat to progress is not only an economic concern. Indigenous

communities are facing an acute public health crisis in the midst of a

financial crisis. We’ve seen that racially marginalized communities experience

disproportionately high rates of infection and mortality, a phenomenon that has

been linked

to social inequities. Many Indigenous communities across North

America are particularly

vulnerable to COVID-19 due to overcrowded living conditions, underfunded

health care systems, and the prevalence of pre-existing health conditions. The

high incidence of COVID-19 in Indigenous populations has generated real concern

about loss

of culture and traditions,

in particular as Indigenous communities lose more of their Elders to the

effects of the virus.

Among

Indigenous communities involved in the casino and gaming industry, COVID-19 may

pose an additional set of challenges related to self-determination, or the collective

right to “freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development”

(Article 1 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights). Although

the sovereignty of Indigenous nations is inherent, settler colonialism in North

America has acted to subvert it, either by design or by circumstance.[5] Within

this context, Indigenous gaming emerged, strengthening the means to exercise

sovereignty in law and in practice (Belanger et al., 2013). For many Indigenous

communities, entrance into the casino and gaming industry is an assertion of

sovereignty – an affirmation of their right to govern issues related to

economic development on their homelands, even when those activities are

prohibited by law elsewhere.[6] In

the longer run, economic progress through gaming strengthens political power

and the ability to self-govern effectively. Although the relationship between

economic growth and sovereignty is complex,[7] one

thing is clear: the COVID-19 shock has implications that extend well beyond

revenue loss for Indigenous gaming communities. In contrast, gaming cities like

Las Vegas and Atlantic City may be susceptible to severe economic ramifications

but they are unlikely to endure domestic political ramifications.

Throughout

the pandemic, Indigenous communities have leveraged their

sovereign status to enact regulations and implement policies to protect

their citizens. Even in the absence of state or provincial safety measures,

Indigenous nations have implemented curfews and lockdowns, set up call centers

and incident command systems, and created highway checkpoints. By the same

token, sovereignty gives Indigenous nations the option to forgo safety measures

that have been put in place by the state, provincial, or federal government.

Indigenous communities may decide to keep their casinos open even when other

commercial casinos have been forced to close. This has left many gaming

communities with a

difficult choice between the health of their community members and

their economic stability. Yet, in reality, when casino revenues fund tribal

services like health care, are these options separable?

The Road Ahead

The

COVID-19 pandemic further exposes the known precariousness of an economy that

lacks diversification. Any locality that is heavily reliant on the casino and

gaming industry is likely to be particularly hard-hit by the COVID-19 shock.

Without being able to observe the economic portfolios of all Indigenous gaming

communities, it seems safe to say that many Indigenous communities in North

America have come to depend on the industry that has been called “the new

buffalo.” On the surface, the worrying implication of the “new buffalo” analogy

is that the COVID-19 shock will have severe consequences for casino-reliant

communities, just as the slaughter of the bison had for bison-reliant

communities. However, deeper analysis shows where the parallelism ends between

the bison and the casinos. Bison were more than a source of livelihood. They

played a central role in the traditions and culture of the peoples who depended

on them. In contrast, as described by Manitowabi (2017), casinos are economic

tools with tenuous connections to culture.[8]

So

what is the future of the Indigenous gaming industry in the wake of the

COVID-19 pandemic? It may be too early to say. But if history is any

indication, there’s reason to remain optimistic. In 2005, Hurricane Katrina

devastated the Mississippi Gulf Coast, another region of importance to the

casino and gaming industry. Casinos along the Gulf Coast closed in anticipation

of the storm. Many remained closed in the aftermath, after incurring major

structural damage (Ewing et al., 2009). As with COVID-19, communities had lost

their major source of employment overnight. But after announcing their plans to

rebuild, casinos proved to be “an anchor” for regional recovery efforts (p. 2).

Perhaps casinos will be at the forefront of COVID-19 recovery as well.

For

many Indigenous communities coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic, the road ahead

will be winding. Indigenous peoples across North America have a long history of

resilience in the face of extreme adversity. That resilience derives from

adaptation. Feir et al. (2019) argue that bison-reliant communities suffered

persistent, negative economic and health outcomes in large part because federal

restrictions designed to protect settler-colonial interests prevented

Indigenous peoples from adjusting to new conditions.[9]

One lesson for the present day is that Indigenous communities may be able to

absorb the COVID-19 shock by continuing to assert their sovereignty to develop

individualized strategies to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. Because of the

nature of the COVID-19 shock, the most effective strategies will target both

demand and supply. And in the long-run, both gaming and non-gaming communities

should continue to diversify their local economies as insurance against future shocks.

Laurel Wheeler is an Assistant

Professor in the Department of Economics at the University of Alberta. As a

labor and development economist, her research addresses issues of poverty and

inequality in low-income countries and in North America.

References:

Akee,

R.K.Q, Spilde, K.A., and Taylor, J.B. (2015). The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act

and its effects on American Indian economic development. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(3): 185-208.

American

Gaming Association. (June 2020). Commercial

gaming revenue tracker. Retrieved from: https://www.americangaming.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/2020-Q2-Commercial-Gaming-Revenue-Tracker.pdf

The

Atlantic. (May 2016). ‘Kill every buffalo you can! Every buffalo dead is an

Indian gone.’ Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2016/05/the-buffalo-killers/482349

Belanger, Y.D. (2014). Are Canadian

First Nations casinos providing maximum benefits? Appraising First Nations

casinos in Ontario, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, 2006-2010. UNLV Gaming Research & Review Journal, 18(2): 65-84.

Belanger, Y.D., Williams, R.J., and

Arthur, J.N. (2013). Manufacturing regional disparity in the pursuit of

economic equality: Alberta’s First Nations gaming policy, 2006-2010. The Canadian Geographer, 57(1): 11-30.

Brinca, P, Duarte, J. B. and Faria-e-Castro, M. (2020), “Measuring

sectoral supply and demand shocks during COVID-19”, Covid Economics, Issue 20, London: CEPR Press.

The

Brookings Institute. (March 2020). The

places a COVID-19 recession will likely hit hardest. Retrieved from: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2020/03/17/the-places-a-covid-19-recession-will-likely-hit-hardest/

Capital & Main. (2020). Tribal casinos weigh dueling risks of

COVID-19, economic ruin. Retrieved from: https://capitalandmain.com/tribal-casinos-weigh-risks-of-covid-19-economic-ruin-0823

Cattelino, J. (2008). High stakes: Florida Seminole gaming and sovereignty.

Duke University Press: Durham, N.C.

Cattelino, J. (2010). The double

bind of American Indian need-based sovereignty. Cultural Anthropology, 25(2): 235-262.

Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (August 2020). COVID-19 among

American Indian and Alaska Native Persons – 23 States, January 31 – July 3,

2020. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6934e1.htm

Chicago

Booth Review. (2020). How COVID-19

shocked both supply and demand. Retrieved from: https://review.chicagobooth.edu/economics/2020/article/how-covid-19-shocked-both-supply-and-demand

Ewing,

B.T., Kruse, J.B., and Sutter, D. (2009). Hurricane Katrina and economic loss. Journal of Business Valuation and Economic

Loss Analysis, 4(2): 1.

Feir, D., Gillezeau, R., and Jones,

M. E. C. (2019). The slaughter of the bison and reversal of fortunes on

the great plains. No. 1-2019. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

Harvard Kennedy Schoo0.l (2020). COVID-19 has closed tribal casinos and cut

off other vital revenue sources – Joseph Kalt. Retrieved from: https://www.hks.harvard.edu/centers/mrcbg/programs/growthpolicy/covid-19-has-closed-tribal-casinos-and-cut-other-vital-revenue

Guerrieri, V., Lorenzoni, G., Straub,

L., and Werning, I. (2020). “Macroeconomic Implications of COVID-19: Can Negative

Supply Shocks Cause Demand Shortages?” Working paper, April 2020

Lane, A. I. (1995). Return

of the buffalo: The story behind America's Indian gaming explosion.

Greenwood Publishing Group.

Manitowabi, D. (2011). Casino Rama: First Nations

self-determination, neoliberal solution, or partial middle ground? (Y.D.

Belanger, Ed.) Univ of Manitoba Press.

Manitowabi, D. (2017). Masking

Anishinaabe Bimaadiziwin. Uncovering cultural

representation at Casino Rama. In B. Gercken & J. Pelletier (Eds.), Gaming, the noble savage, and the not-so-new

Indian (pp. 105-118).

Marshall, M. (2019). First Nations gaming in Canada:

Navigating the labyrinth. Gaming Law Review, 23(8),

559-571.

Meister Economic

Consulting. (2020). Coronavirus impact on

tribal gaming. Retrieved from: http://www.meistereconomics.com/coronavirus-impact-on-tribal-gaming

National

Indian Gaming Commission. (2020). Gross gaming

revenue reports. Retrieved from: https://www.nigc.gov/commission/gaming-revenue-reports

Native

Governance Center. (2020). How does

tribal sovereignty operate during COVID-19? Retrieved from: https://nativegov.org/tribal-sovereignty-and-covid-19/

The

New York Times. (2020). Social inequities

explain racial gaps in pandemic, studies find. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/09/health/coronavirus-black-hispanic.html

The

New York Times. (May 2020). Tribal

nations face most severe crisis in decades as the coronavirus closes casinos.

Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/11/us/coronavirus-native-americans-indian-country.html

NPR.

(May 2020). Navajo Nation loses Elders

and tradition to COVID-19. Retrieved from: https://www.npr.org/2020/05/31/865540308/navajo-nation-loses-elders-and-tradition-to-covid-19

Reuters.

(June 2020). Loss of Canada Elders to

coronavirus threatens Indigenous culture. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-canada-indigenous/loss-of-canada-elders-to-coronavirus-threatens-indigenous-culture-idUSKBN2382D4

S&P Market

Intelligence. (March 2020). Industries

most and least impacted by COVID-19 from a probability of default perspective –

March 2020 Update. Retrieved from: https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/blog/industries-most-and-least-impacted-by-covid-19-from-a-probability-of-default-perspective-march-2020-update

S&P Market

Intelligence. (September 2020). Industries

most and least impacted by COVID-19 from a probability of default perspective –

September 2020 Update. Retrieved from: spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/blog/industries-most-and-least-impacted-by-covid19-from-a-probability-of-default-perspective-september-2020-update

Stevens,

Rhys. (March 2020). The impact of

COVID-19 on gambling availability. Retrieved from: https://abgamblinginstitute.ca/files/abgamblinginstitute/canada_commercial_gambling_closures_covid-19_by_province_march_25_2020.pdf

The United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. International covenant on civil and political

human rights. Retrieved from: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CCPR.aspx

Vox. (2020). The coronavirus is

exacerbating vulnerabilities Native communities already face. Retrieved

from: https://www.vox.com/2020/3/25/21192669/coronavirus-native-americans-indians

Vox EU. (2020). Decomposing demand

and supply shocks during COVID-19. Retrieved from: https://voxeu.org/article/decomposing-demand-and-supply-shocks-during-covid-19

Wheeler, L. (2019). Property

rights, place-based policies, and economic development. US Census Bureau

working paper series, Center for Economic Studies.

The Wisconsin State Journal. (2020). Tribal

governments ‘crippled’ by lost gambling revenue during COVID-19 pandemic. Retrieved

from: https://madison.com/wsj/business/tribal-governments-crippled-by-lost-gambling-revenue-during-covid-19-pandemic/article_67265db9-1dfa-53c4-b78c-5e462737819e.html

Zandi, M. (March 2020). COVID-19: A Fiscal Stimulus Plan. Retrieved from: https://www.economy.com/economicview/analysis/378644/COVID19-A-Fiscal-Stimulus-Plan

[1] See,

for example, Lane (1995). As Cattelino (2008) points out, the “new buffalo”

motif falls short in some respects. Importantly, the imagery inaccurately

suggests that entrance into the casino and gaming industry is a passive action,

something that “acts upon” Indigenous communities, rather than an action taken

by Indigenous communities based on economic, political, and cultural incentives

(p. 29).

[2] This is, of course,

abstracting away from non-traditional options such as online gambling.

[3] Physical measures such as height are often

used as non-economic indicators of well-being. Feir et al. (2019) find that the

descendants of bison-reliant peoples are shorter due to the slaughter of the

bison, suggesting that their well-being was impacted through a mechanism such

as malnutrition.

[4] The slaughter of

the bison did not only affect bison-reliant communities through economic

channels. Bison were integrated into the fabric of Indigenous society. The

intentional destruction of the bison was both an economic act and a

socio-cultural one.

[5] As one example,

U.S. federal policy in the Termination Era (from the 1940s-1960s) sought to

forcibly assimilate Indigenous people by eradicating federal reservations,

terminating treaty obligations to Indigenous nations, and ending government aid

programs.

[6] This perspective is

more likely to be relevant in the U.S. context than the Canadian context.

Canada does not recognize that First Nations have a right to participate in the

casino and gaming industry in the way that the United States does (Marshall,

2019). Instead, pursuant to the 1985 Criminal Code of Canada, First Nations

must enter into agreements with provinces.

[7] In fact, economic

growth may simultaneously strengthen the means to exercise sovereignty and

undermine sovereignty (Cattelino, 2010). For example, the U.S. federal

government used economic strength as way to target tribes for Termination Era

policies, based on the idea that the communities with the strongest economies

no longer needed a collective agreement with the federal government. Cattelino

calls this approach “need-based sovereignty,” which puts Indigenous communities

in the untenable position of being unable to exercise sovereignty without

economic power and yet challenged about the legitimacy of their sovereignty

given economic power.

[8] Through a case

study of Casino Rama, Manitowabi (2017) illustrates how Indigenous casinos may

employ cultural stereotypes of indigeneity for marketing purposes rather than

for the purposes of genuine cultural expression.

[9] Specifically, Feir

et al. (2019) suggest that federal restrictions on mobility and economic

diversification precluded communities from making adjustments to economic

shocks.

Comments

Post a Comment